Sometime in the next few years—no one knows exactly when—three NASA satellites, each as heavy as an elephant, will plunge into darkness.

They are already drifting, losing height bit by bit. They’ve been watching the planet for more than two decades, much longer than expected, helping us predict the weather, manage wildfires, monitor oil spills and much more. But age is catching up with them, and soon they will send their last transmissions and begin their slow, final fall to Earth.

This is a moment scientists dread.

When the three orbiters—Terra, Aqua, and Aura—are shut down, much of the data they’ve been collecting will be gone, and the newer satellites won’t be able to pick up all the work. Researchers will either have to rely on alternative sources that may not meet their exact needs or seek workarounds to allow their records to continue.

With some of the data these satellites collect, the situation is even worse: no other instruments will continue to collect it. In a few short years, the subtleties they reveal about our world will become much more blurred.

“The loss of this irreplaceable data is just tragic,” said Susan Solomon, an atmospheric chemist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Just when the planet most needs us to focus on understanding how we are affected by it and how we impact it, we seem to have fallen catastrophically asleep at the wheel.”

The main area we lose sight of is the stratosphere, the most important home of the ozone layer.

In the cold, rarefied air of the stratosphere, ozone molecules are constantly being formed and destroyed, shed and swept away as they interact with other gases. Some of these gases have a natural origin; others are there for us.

Aura’s instrument, the Microwave Limb Probe, gives us the best line of sight into this simmering chemical drama, said Ross J. Salavitch, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Maryland. Once the aura wears off, our vision will blur considerably, he said.

Recently, the microwave limb probe data has proven its value in unexpected ways, Dr. Salavic said. It showed how much damage was done to the ozone by the devastating bushfires in Australia in late 2019 and early 2020 and by the underwater volcanic eruption near Tonga in 2022. It helped show how much ozone-depleting pollution is rising in stratosphere over East Asia from the summer monsoon in the region.

If it doesn’t go offline so soon, the probe could also help unravel a major mystery, Dr Salavic said. “The thickness of the ozone layer over populated regions in the Northern Hemisphere has barely changed over the past decade,” he said. “He has to recover. And it isn’t.”

Jack Kay, associate director of research in NASA’s Earth Science Division, acknowledged researchers’ concerns about the probe’s end. But he argued that other sources, including instruments on newer satellites, on the International Space Station and back here on Earth, would still provide “a pretty good window into what the atmosphere is doing.”

Financial realities are forcing NASA to make “difficult decisions,” Dr. Kay said. “Would it be great if everything lasted forever? Yes, he said. But part of NASA’s mission is also to offer scientists new tools that help them look at our world in new ways, he said. “It’s not the same, but, you know, if everything can’t be the same, you do the best you can,” he said.

For scientists studying our changing planet, the difference between the same data and nearly identical data can be huge. They may think they understand how something develops. But only by observing it continuously, in an unchanging way, over a long period of time, can they be sure what is going on.

Even a short break in recordings can cause problems. Let’s say an ice shelf collapses in Greenland. Unless you measured sea-level rise before, during and after, you’ll never be sure that the sudden change was caused by the collapse, said William B. Gale, past president of the American Meteorological Society. “You can assume it, but you don’t have quantitative data,” he said.

Last year, NASA canvassed scientists for thoughts on how the end of Terra, Aqua and Aura would affect their work. Over 180 of them responded to the call.

In their letters, obtained by The New York Times through a Freedom of Information Act request, the researchers expressed concerns about a wide range of satellite data. Information on particles in wildfire smoke, desert dust and volcanic plumes. Cloud thickness measurements. Small-scale maps of the world’s forests, grasslands, wetlands and crops.

Even if there are alternative sources for this information, the researchers write, they may be less frequent or of lower resolution or limited to certain times of day, all factors that determine how useful the data are.

Liz Moyer takes a close-up approach to studying Earth’s atmosphere: by flying instruments through it, on jets that travel much higher than most airplanes can lift. “I got into it because it’s exciting and it’s hard to get there,” said Dr. Moyer, who teaches at the University of Chicago. “It’s hard to build instruments that work there, it’s hard to make measurements, it’s hard to get airplanes to go there.”

It would be even more difficult after Aura was gone, she said.

Airplanes can directly sample the chemical composition of the atmosphere, but to understand the big picture, scientists still need to combine measurements from the airplane with satellite readings, Dr. Moyer said. “Without the satellites, we’re out there taking snapshots without context,” she said.

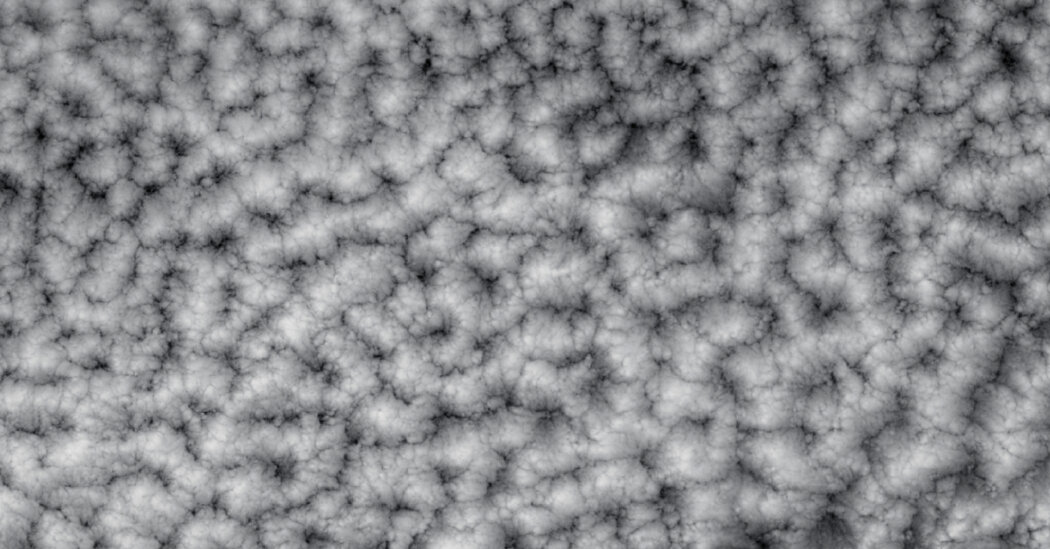

Much of Dr. Moyer’s research has focused on the thin, icy clouds that form nine to 12 miles above the ground, in one of the atmosphere’s most mysterious layers. These clouds are helping to warm the planet, and scientists are still trying to understand how human-induced climate change is affecting them.

“It looks like we’re just going to stop observing this part of the atmosphere, and just as it’s changing,” Dr Moyer said.

The end of Terra and Aqua will affect how we observe another important driver of our climate: how much solar radiation the planet receives, absorbs and bounces back into space. The balance between these quantities – or actually the imbalance – determines how much the Earth warms or cools. And to find out, scientists are relying on NASA’s Cloud and Earth’s Radiant Energy System, or CERES, instruments.

Four satellites are currently flying with the CERES instruments: Terra, Aqua plus two newer ones that are also nearing completion. Still, only one replacement is in the works. Its life expectancy? Five years.

“Within the next 10 years, we’ll go from four missions to one, and the one that’s left will be in full swing,” said Norman G. Loeb, the NASA scientist who directs CERES. “It’s really sobering for me.”

These days, with the rise of the private space industry and the proliferation of satellites around Earth, NASA and other agencies are exploring a different approach to keeping an eye on our planet. The future may be smaller, lighter instruments, ones that can be launched into orbit cheaper and more nimbly than Terra, Aqua and Aura in their day.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is developing such a fleet to monitor weather and climate. Dr. Loeb and others at NASA are working on a lightweight instrument to continue measurements of Earth’s energy balance.

But for such technologies to be useful, Dr. Loeb said, they must begin flying before today’s orbiters go dark.

“You need a good, long period of overlap to understand the differences, to work out the kinks,” he said. “If not, then it’s going to be really hard to trust those measurements if we haven’t had a chance to prove them against current measurements.”

In some ways, it’s to NASA’s credit that Terra, Aqua and Aura have lasted so long, the scientists said. “Through a mixture of excellent engineering and a tremendous amount of luck, we’ve had them for 20 years now,” said Walid Abdalati, a former NASA chief scientist now at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“We’ve become addicted to these satellites. We are victims of our own success,” said Dr. Abdalati. “Eventually,” he added, “luck wears off.”