Boeing needs a few extra days to resolve a small helium leak in the Starliner spacecraft designed to carry two NASA astronauts on a test flight to the International Space Station, officials said Tuesday.

That means the first crewed launch of Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft, which is years behind schedule and more than $1.4 billion over budget, won’t happen until next Tuesday, May 21, at 4:43 p.m. EDT (8:43 p.m. UTC). Adherence to this schedule implies that engineers can be comfortable with helium leakage. Officials from Boeing and NASA, which manages Boeing’s multibillion-dollar contract for Starliner’s commercial crew, had previously targeted Friday, May 17, for the spacecraft’s first launch with astronauts aboard.

Boeing’s ground team traced the leak to a flange of one thruster of the reaction control system on the spacecraft’s service module.

There are 28 reaction control system thrusters – essentially small rocket engines – on the Starliner Service Module. In orbit, these thrusters are used to make small course corrections and point the spacecraft in the right direction. The service module has two sets of more powerful thrusters for greater orbit corrections and launch abort maneuvers.

The spacecraft’s propulsion system is pressurized using helium, an inert gas. The engines burn a mixture of toxic hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide. Helium is not flammable or toxic, so a small leak probably wouldn’t pose a serious safety problem on earth, but the propulsion system must maintain pressure for the thrusters to operate in space.

A number of technical setbacks have prevented Boeing’s Starliner program from reaching this point until now. These failures included a fuel leak on a test stand, software problems on the Starliner’s first unmanned test flight, and corroded valves in the spacecraft’s propulsion system. In the run-up to last summer’s launch attempt, Boeing and NASA discovered two more problems — flammable material in the capsule and a weak connection in the Starliner’s parachute system — that delayed the crewed test flight by nearly a year.

According to NASA, engineers plan to address the helium leak using “spacecraft testing and operational solutions.” In other words, managers do not foresee a need to physically fix the leak.

“As part of the testing, Boeing will bring the propulsion system to flight pressurization, just as it does before launch, and then allow the helium system to vent naturally to confirm existing data and improve flight justification,” officials wrote of NASA in a blog post Tuesday. The flight rationale is spoken by NASA about gaining confidence in understanding a problem and a comfortable feeling that it will not pose additional risk during flight.

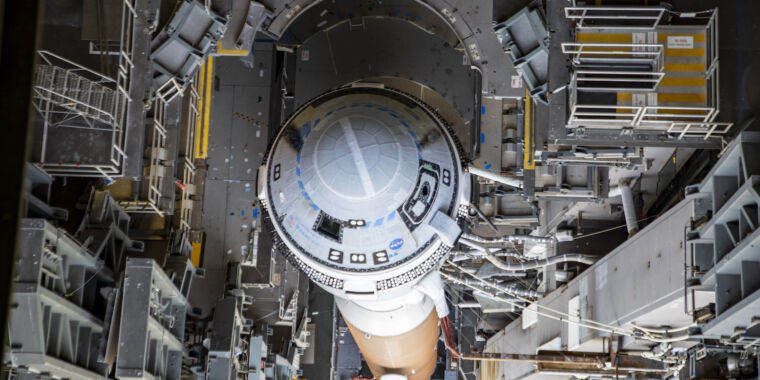

The rocket is ready

A valve failure on the Atlas V rocket designed to launch Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule aborted the first launch attempt for the crew test flight on May 6 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida. United Launch Alliance, the company that builds and operates the Atlas V, moved the rocket and Starliner off the launch pad and back into a hangar last week to replace a faulty pressure control valve on the top of the Atlas V’s Centaur.

Once installed on the rocket, the new valve performed normally in tests at the ULA hangar. ULA will return the rocket back to the launch pad a few days before the next launch attempt.

“Mission teams have also completed a thorough review of data from the May 6 launch attempt and are not tracking any other issues,” NASA said.

NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Sunny Williams, commander and pilot of the Starliner test flight, returned to their home base in Houston to spend more time with their families and wait for the next mission launch date. They will return to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida in the coming days for final preparations for launch, NASA said.

Wilmore and Williams, both US Navy test pilots, will monitor the Starliner’s systems from launch to docking with the International Space Station. Their tasks included taking manual control of the Boeing crew capsule for a series of pilot demonstrations. If all goes according to plan, they will spend at least eight days on the space station before returning to Earth in the Starliner spacecraft for a parachute and hovercraft landing in the southwestern United States, possibly in White Sands, New Mexico.

Their stay on the space station may be extended to wait for good weather at one of the Starliner landing sites. With the upcoming Starliner flight, the United States will have, for the first time since the dawn of the space age, two independent, human-rated spacecraft capable of flying humans into low Earth orbit. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, which won NASA’s commercial crew contract at the same time as Boeing in 2014, began flying astronauts in 2020.

NASA’s commercial crew contract with Boeing covers six operational crew rotation flights to and from the space station. A successful test flight with Wilmore and Williams will pave the way for the Starliner to fly the first of these six-month crewed missions early next year.