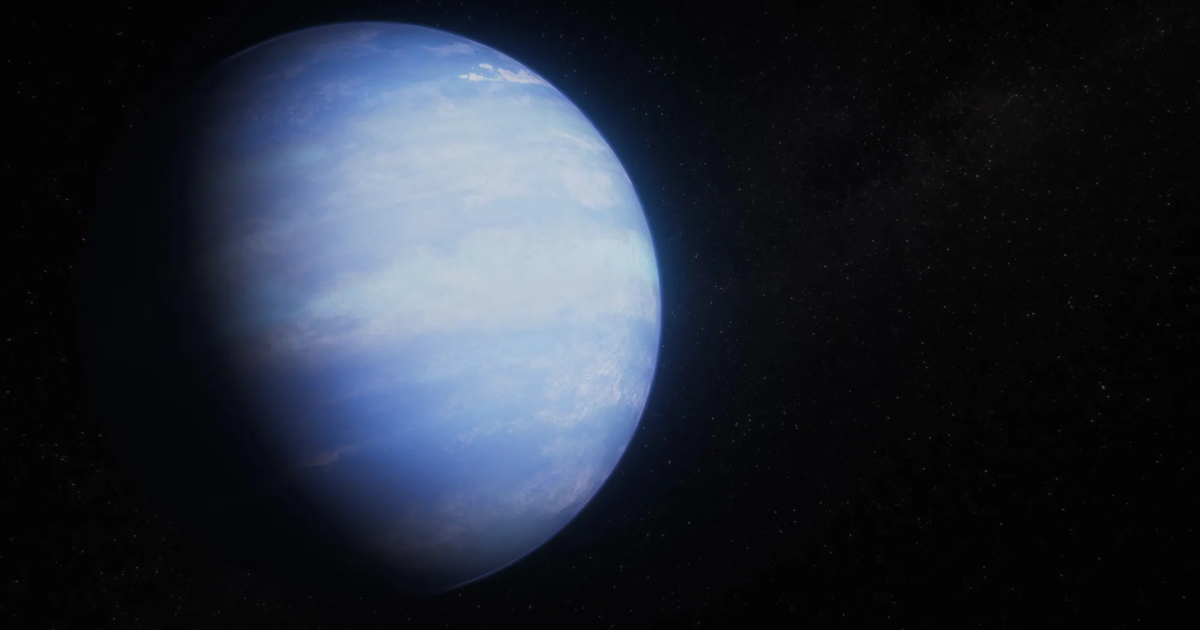

Astronomers believe they have solved a peculiar and well-established space mystery, NASA announced this week. Mainly using observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, two groups of researchers may have discovered what makes certain planets tick look “bloated” or bloated far beyond the dimensions their remarkably low densities suggest.

It’s a phenomenon that appears to be down to the surprising interior composition of exoplanets like WASP-107b, a “warm Neptune” gas giant identified in 2017 that orbits a star about 200 light-years from Earth. Although scientists have already identified thousands of low-density exoplanets, this one is different from the “hot Jupiters” and even the unusual “hot Neptunes” previously studied.

Astronomers looked at WASP-107b’s structure in hopes of understanding how it could be so massive while weighing so little, as they assumed based on features like its size and distance from its star that it was cooler internally than it turned out to be .

“Based on the radius, mass, age and assumed internal temperature, we decided that WASP-107 b has a very small, rocky core surrounded by a huge mass of hydrogen and helium,” said Louis Welbanks of Arizona State University, who led one of the new exoplanet research, in a statement to NASA. “But it was hard to understand how such a small core could absorb so much gas and then stop developing completely into a Jupiter-mass planet.”

NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralph Crawford (STScI)

WASP-107b is almost the size of Jupiter, but only about one-tenth as dense. The exoplanet weighs about 30 Earths, while Jupiter weighs more than 300, making WASP-107b one of the least dense planets known, NASA said. This was strange because it is less hot and less massive than other “fluffy” exoplanets, such as the Jupiter-like deep-space gas giant WASP-193b, which was discovered last year and also noted for its extremely low density.

Although there is no evidence-based explanation for the puffiness of larger, hotter exoplanets, scientists said WASP-107b is particularly difficult to explain because it does not collect enough energy from the star it orbits for the gases, that make her puff up so much. But new data from Webb, combined with older data from the Hubble Space Telescope, revealed another reason for its expansion.

The telescope’s observations found only a fraction of the methane gas that astronomers expected to find in WASP-107b’s atmosphere, which “tells us that the interior of the planet must be significantly hotter than we thought,” said David Singh of the university Johns Hopkins, who led a second new study of WASP-107b.

This supports a theory previously proposed by astronomers about why WASP-107b is “bloated”, suggesting that a process called tidal heating is responsible for both the higher internal temperature and the bloated size. Learning about WASP-107b’s atmosphere could also provide crucial insight into dozens of other low-density “bloated” planets and what causes them to expand, potentially helping to clarify what NASA has called “a long-standing mystery in exoplanet science.” .