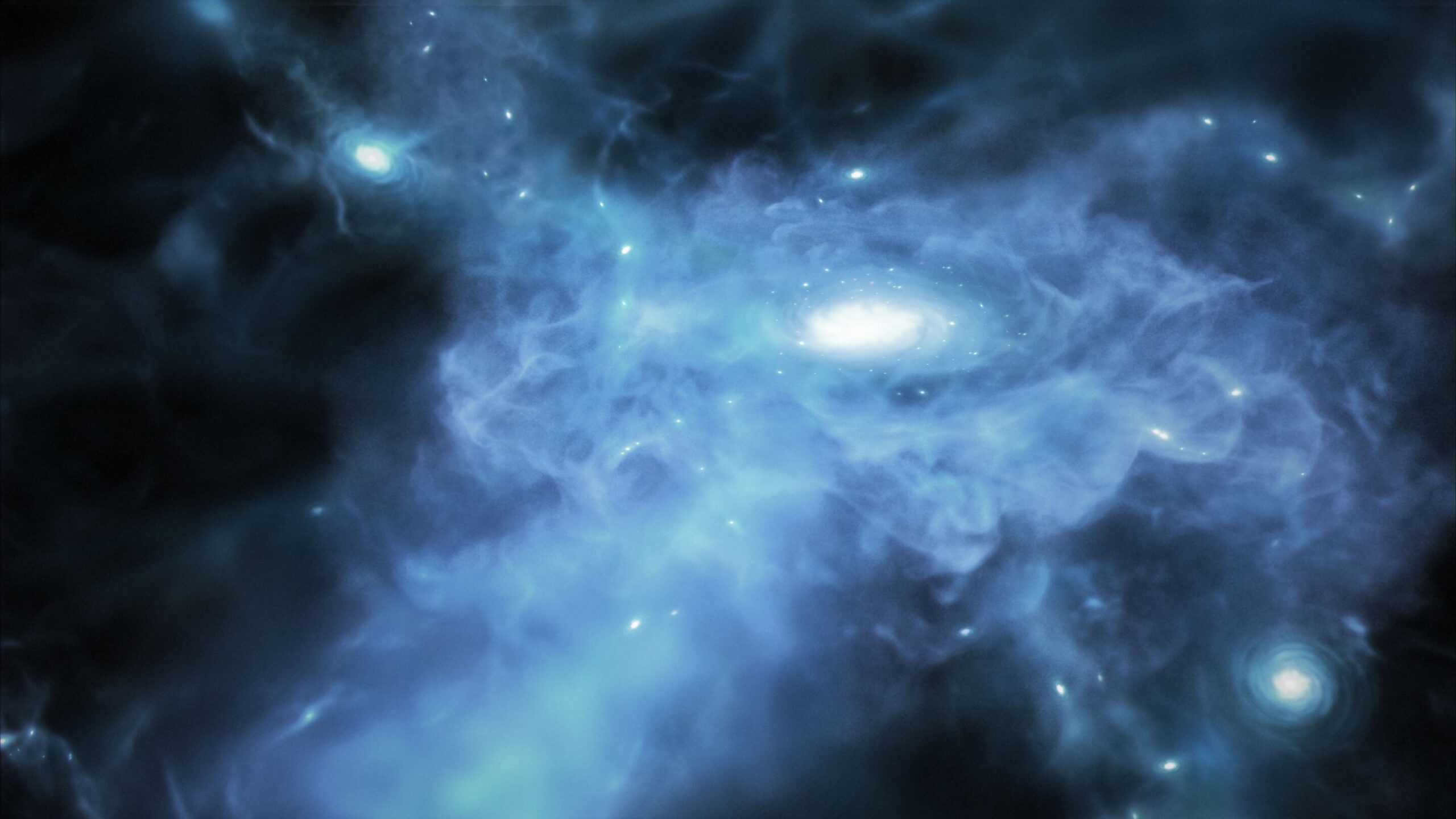

Gas accreting and accreting onto a forming mini-galaxy. Although this is how galaxies form according to theories and computer simulations, it has never been observed. Credit: NASA

× near

Gas accreting and accreting onto a forming mini-galaxy. Although this is how galaxies form according to theories and computer simulations, it has never been observed. Credit: NASA

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, researchers from the University of Copenhagen became the first to see the formation of three of the earliest galaxies in the universe more than 13 billion years ago. The sensational discovery contributes to important knowledge about the universe and has now been published in Science.

For the first time in the history of astronomy, researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute witnessed the birth of three of the absolute earliest galaxies in the universe, somewhere between 13.3 and 13.4 billion years ago.

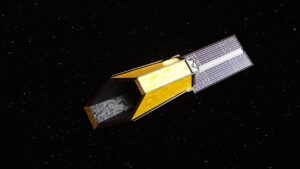

The discovery was made using the James Webb Space Telescope, which brought these first “live observations” of forming galaxies to us here on Earth.

Through the telescope, the researchers were able to see signals from large amounts of gas accreting and accreting onto the forming mini-galaxy. Although this is how galaxies form according to theories and computer simulations, it has never been observed.

“These are arguably the first ‘direct’ images of galaxy formation we’ve ever seen. While James Webb previously showed us early galaxies at later stages of evolution, here we witness their very birth and thus building the first star systems in the universe,” says Assistant Professor Kasper Elm Heinz of the Niels Bohr Institute, who led the new study.

Galaxies born shortly after the Big Bang

Researchers estimate that the birth of the three galaxies occurred roughly 400-600 million years after the Big Bang, the explosion that started it all. Although this sounds like a long time, it corresponds to galaxies forming in the first 3–4% of the universe’s 13.8 billion years of total life.

Shortly after the Big Bang, the universe was a vast, opaque gas of hydrogen atoms—unlike today, where the night sky is dotted with a blanket of well-defined stars.

“During the few hundred million years after the Big Bang, the first stars formed before the stars and gas began to merge into galaxies. This is the process we see the beginnings of in our observations,” explains Associate Professor Darach Watson.

The birth of galaxies occurred at a time in the history of the universe known as the Age of Reionization, when the energy and light of some of the first galaxies broke through the haze of hydrogen gas.

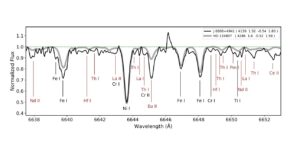

It was these large amounts of hydrogen gas that were captured by the researchers using the infrared vision of the James Webb Space Telescope. This is the most distant measurement of the cold, neutral hydrogen gas that is the building block of stars and galaxies discovered by scientists to date.

Contributes to the understanding of our origins

The study was conducted by Kasper Elm Heintz, in close collaboration with – among others – fellow researchers Darach Watson, Gabriel Brammer and Ph.D. student Simone Veilgaard of the Cosmic Dawn Center at the University of Copenhagen’s Niels Bohr Institute, a center whose stated goal is to study and understand the dawn of the universe. This latest result brings them much closer to that.

The research team has already applied for more observing time with the James Webb Space Telescope, hoping to expand on their new result and learn more about the earliest era in galaxy formation.

“For now, it’s about mapping our new observations of galaxies forming in even greater detail than before.” At the same time, we are constantly trying to push the limit of how far into the universe we can see. So, maybe we’ll go even further,” says Weilgaard.

According to the researcher, the new knowledge contributes to an answer to one of the most basic questions of humanity.

“One of the most fundamental questions humans have always asked is, ‘Where did we come from?'” Here, we piece together a little more of the answer by shedding light on when some of the universe’s first structures were created. This is a process that we will explore further as we hope to be able to put even more pieces of the puzzle together,” concludes Assoc. Brammer.

The study was conducted by researchers Kasper E. Heintz, Darach Watson, Gabriel Brammer, Simone Vejlgaard, Anne Hutter, Victoria B. Strait, Jorryt Matthee, Pascal A. Oesch, Pall Jakobsson, Nial R. Tanvir, Peter Laursen, Rohan P. Naidu , Charlotte A. Mason, Meghana Kiley, Intae Jung, Tiger Yu-Yang Hsiao, Abdurro’ouf, Dan Kou, Pablo Arabal Haro, Steven L. Finkelstein, and Sune Toft.

More info:

Kasper E. Heintz, Strongly quenched Lyman-α absorption in young star-forming galaxies at redshifts 9 to 11, Science (2024). DOI: 10.1126/science.adj0343. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adj0343

Log information:

Science