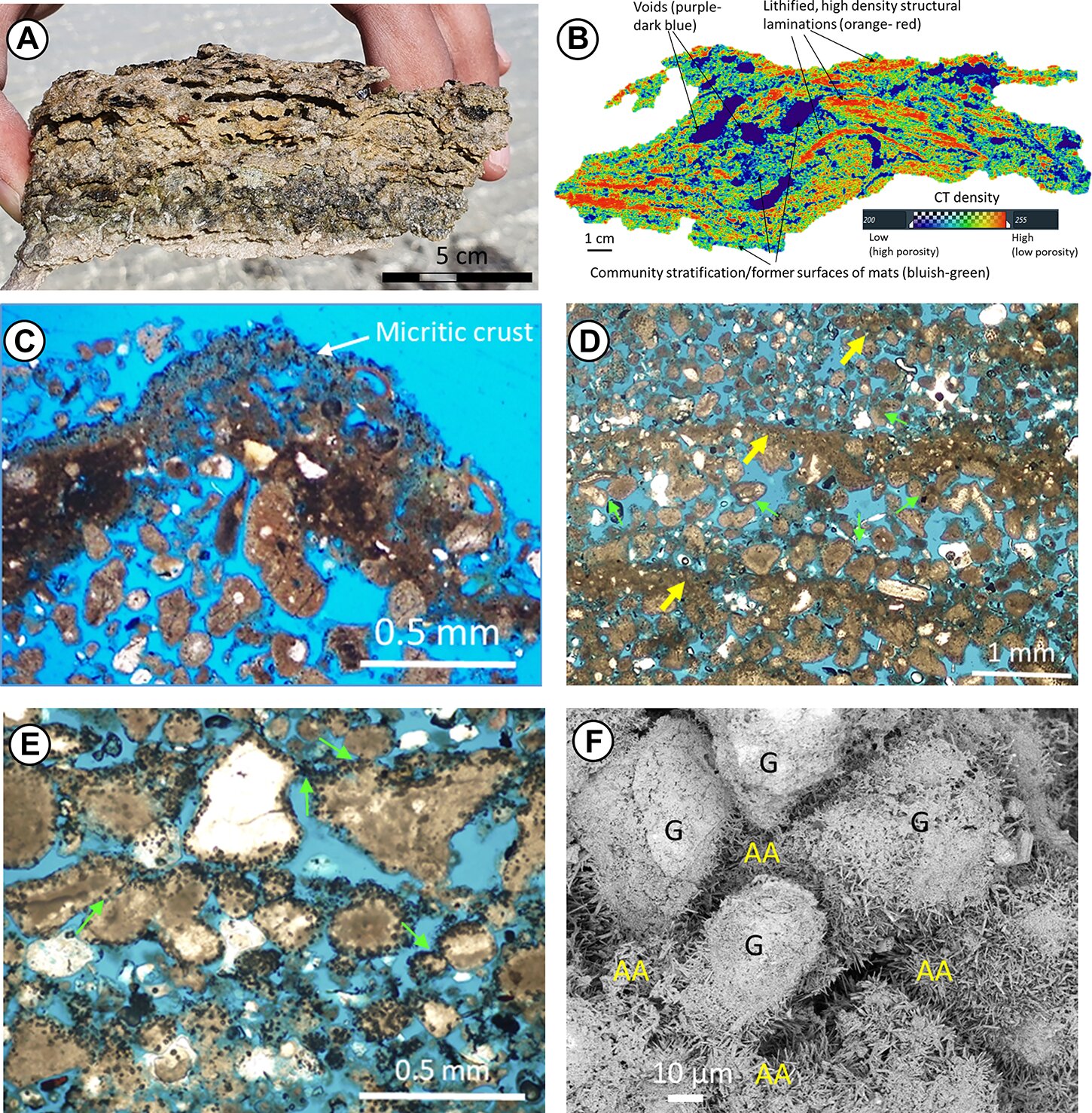

(A) Hand sample of type 1 stromatolite showing layered structures. (B) X-ray microcomputed tomography (μCT) XZ image of a cross-section of a type 1 stromatolite, exposing denser internal laminations (red). The color bar represents a range of μCT values corresponding to CT density; blue = void. (C) Thin-section photomicrograph illustrating micritic crust on the surface of the stromatolite. (D) Millimeter-scale lithified sedimentary grain layers (yellow arrows) and melt grains (green arrows). (E) Grains infected with microprobes near the outer edges and fused at the grain contacts (green arrows). (F) Acicular aragonite cements (AA) formed around grain rims (G). credit: Geology (2024). DOI: 10.1130/G51793.1

× near

(A) Hand sample of type 1 stromatolite showing layered structures. (B) X-ray microcomputed tomography (μCT) XZ image of a cross-section of a type 1 stromatolite, exposing denser internal laminations (red). The color bar represents a range of μCT values corresponding to CT density; blue = void. (C) Thin-section photomicrograph illustrating micritic crust on the surface of the stromatolite. (D) Millimeter-scale lithified sedimentary grain layers (yellow arrows) and melt grains (green arrows). (E) Grains infected with microprobes near the outer edges and fused at the grain contacts (green arrows). (F) Acicular aragonite cements (AA) formed around grain rims (G). credit: Geology (2024). DOI: 10.1130/G51793.1

Stromatolites are the earliest geological record of life on Earth. These curious biotic structures are made of carpets of algae growing towards the light and precipitating carbonates. After their first appearance 3.48 Ga ago, stromatolites dominated the planet as the only living carbonate factory for almost three billion years.

Stromatolites are also partially responsible for the Great Oxygen Event, which dramatically changed the composition of our atmosphere by introducing oxygen. This oxygen initially outcompeted the stromatolites, allowing them to emerge in Archean and early Proterozoic environments. However, as more life forms adapted their metabolism to an oxygen-rich atmosphere, stromatolites began to decline, appearing in the geologic record only after mass extinctions or in harsh environments.

“Bacteria are always around, but they usually don’t have the chance to make stromatolites,” explains Volker Warenkamp, author of a new study in Geology. “They’ve largely been overtaken by corals.”

In modern times, stromatolites have been moved to niche extreme environments, such as hypersaline marine conditions (e.g. Shark Bay, Australia) and alkaline lakes. Until recently, the only known modern analogue of the biologically diverse, open shallow marine conditions where most Proterozoic stromatolites developed were the Exuma Islands in the Bahamas.

That is, until Varenkamp discovered living stromatolites on Sheybara Island, on the northeastern shelf of the Red Sea in Saudi Arabia. Varenkamp was studying tipi structures — domes of salt crust that can be seen from space — when he came across the nondescript stromatolite field. The discovery was surprising, but fortunately, Vahrenkamp is one of the few people who had previously seen stromatolites in the Bahamas.

“When I stepped on them, I knew what they were,” Varenkamp explains. “It’s 2,000 km of coastline on a carbonate platform, so it’s basically a desirable area to look for stromatolites … but then, it’s the same in the Bahamas, but there’s only one small area where you find them.”

Sheibara Island is an intertidal to shallow subtidal environment, with regularly alternating wetting and drying conditions, extreme temperature fluctuations between 8 °C and >48 °C, and oligotrophic conditions – similar to the Bahamas. As similar environmental conditions are widespread in the Al Wajh carbonate platform, there may be other stromatolite fields nearby. Vahrenkamp and his team have begun this exploratory work, but the stromatolites are small, about 15 cm in diameter, and thus difficult to spot until one gets very close.

There are several hundred stromatolites in the Sheibara Island field. Some are well developed, perfect textbook examples. Others are more leafy, with low relief. “It’s possible they’re young,” Warenkamp hypothesized, “but we don’t know what a baby stromatolite looks like. They probably start small, but we don’t know.’

Part of the problem is that we don’t know how fast stromatolites grow. Dating them is very difficult because they contain two distinct carbonate components that are virtually impossible to separate: the microbial neoprecipitation of interest, and the carbonate sand present in the environment, which is misleading. Vahrenkamp’s team currently monitors the field monthly to record any visual changes. There may soon be an attempt to transfer some stromatolites from Sheibara Island to an aquarium and grow them there – an exciting experimental prospect.

Vahrenkamp’s discovery gives us an opportunity to better understand the formation and growth of stromatolites. This will provide insight into early life and the evolution of Earth’s ocean, and may even help us in our search for life on other planets such as Mars. What would life on Mars look like and how would we recognize it? Looking at stromatolites, which were the first life forms on Earth before our planet even had an oxygen atmosphere, is the most promising avenue.

More info:

Volker Vahrenkamp et al, Discovery of modern living intertidal stromatolites on Shaybara Island, Red Sea, Saudi Arabia, Geology (2024). DOI: 10.1130/G51793.1

Log information:

Geology