The venerable Hubble Space Telescope is running out of gyroscopes, and when there are none left, the instrument will cease to conduct meaningful science.

To preserve the telescope, which has been in space for nearly three and a half decades, NASA announced Tuesday that it will scale back Hubble’s operations to operate with just one gyroscope. This will limit some science operations and take longer to point the telescope at new objects and lock onto them.

But in a conference call with space reporters, Hubble officials stressed that the beloved science instrument isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

“I personally don’t see it as a big limitation on his ability to do science,” said Mark Clampin, director of the astrophysics division at NASA headquarters in Washington.

Six to one

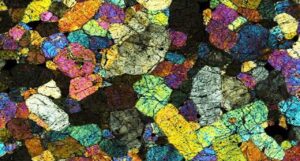

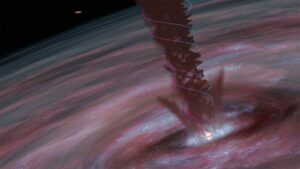

The Hubble Telescope was launched on NASA’s Space Shuttle in 1990, and since then the space agency has conducted five servicing missions to repair and upgrade the complex instrument. To this day, it offers mankind the best view of the universe in the visible light spectrum.

The last of these servicing missions performed by the Space Shuttle Atlantis in 2009, it underwent numerous upgrades, including the replacement of all six gyroscopes that help orient and steer the telescope. However, in the 15 years since then, three of the six gyroscopes have failed. Over the past six months, another, “gyro 3,” has been increasingly returning erroneous data. This caused Hubble to go into safe mode several times, halting science operations.

As a result, the space agency only has two fully functional gyroscopes. One of them, Gyroscope 4, has worked for a total of 142,000 hours. Another, Gyro 6, has accumulated 90,000 hours. NASA’s plan is to now operate the telescope with one gyroscope, with the second remaining as a “backup” option.

NASA has said that operation with a single gyroscope is feasible, with relatively modest implications for observational capabilities. It will be less effective and require more time to target. This will result in a loss of about 12 percent of the monitoring time. The telescope also won’t be able to observe objects closer than Mars, including Venus and the Moon.

However, by taking this step now, the space agency believes it can extend Hubble’s operational life by another decade. The telescope’s project manager, Patrick Kraus, said there is a 70 percent chance Hubble will be able to support science operations using a single gyroscope by 2035.

“We don’t see Hubble being on its last legs,” he said Tuesday.

From a scientific point of view, it is important that Hubble continues to operate. Now that the powerful James Webb Space Telescope is up and running, the two instruments are an unlikely duo. With Hubble observing in visible light and Webb in infrared, astronomers can glean valuable new insights into the nature of the universe.

Another service mission? No thanks

In addition to aging science instruments and a dwindling number of gyroscopes, NASA also faces some other instrument life challenges. The telescope typically operated at altitudes between 615 km and 530 km above the Earth’s surface. However, the telescope is likely to drop below 500 km sometime this year. At lower altitudes, some of the telescope’s observations are affected by other satellites in low Earth orbit.

Clampin said Tuesday that telescope operators do not predict Hubble will re-enter Earth’s atmosphere before the mid-2030s. That, combined with the gyroscope limit, appears to put a hard limit on Hubble’s maximum remaining life.

However, in 2022, Jared Isaacman, a billionaire who managed the first fully commercial human mission to orbit aboard Crew Dragon, approached NASA about conducting a mission to service the Hubble Space Telescope. He offered to fund the bulk of the mission, which would have at least re-enlarged the Hubble Space Telescope by at least 50 km.

After NASA and SpaceX conducted a feasibility study late that year, it was recommended that the space agency continue to explore the possibility of a commercial mission. At the very least, it could safely re-zoom the telescope, but there were also options that included attaching star trackers and external gyroscopes to compensate for the telescope’s ailing guidance system.

But NASA decided not to pursue that option.

“Our position right now is that once we explore the current commercial opportunities, we will not pursue an outright restart,” Clampin said on Tuesday.

Asked about the study, which NASA refused to release for proprietary reasons, Clampin said: “It was a feasibility study to help us understand some of the issues and challenges that we might have to face,” said he. “There were options like being able to make improvements by adding gyroscopes to the outside of the telescope, but those were really just tentative concepts.”

NASA apparently decided it was safer to let Hubble age on its own than to risk private hands touching the hallowed telescope. We’ll see how that goes.