After their father died in 2021, Susan Camp and her brother cleaned out his home — and inadvertently threw away $5,000 in cash that he had wrapped in aluminum foil and stashed in the freezer. (Fortunately, it was later removed.)

And she was surprised, but not shocked, to find $6,000 in a box that once held a bottle of cologne. “Dad was traveling and always wanted money for him,” she said.

Adrienne Volpe’s grandmother kept her extra money in her library.

“My grandmother had thousands of dollars pressed into single book accounts,” Ms. Volpe said. “We thought we’d find fall leaves” between the pages, she said. They had to open every book in the house to find the money she had hidden – about $10,000, it turned out, in only $20 bills.

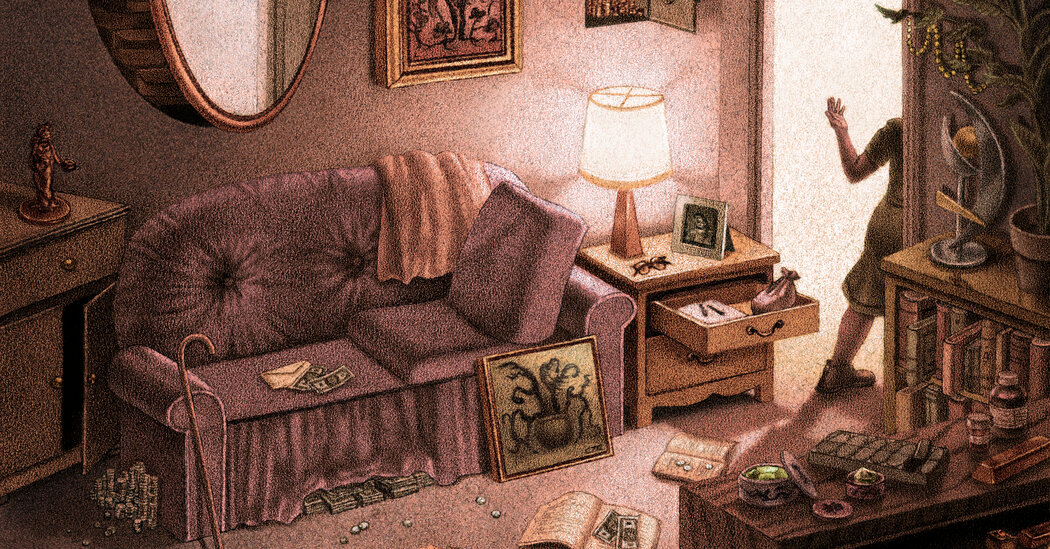

It may not be under the mattress, but for people who come across a small fortune after an elderly relative dies or moves into a nursing home, the disclosure of such unexpected wealth—technically part of a person’s estate—can lead to complications and even conflict.

Often, members of older generations perceive keeping money, gold or other valuables at home as safer than keeping them in a bank, experts say. “I think it’s more common for baby boomers and older,” said Mark Krainer III, senior trust strategist for Baird Trust in Scottsdale, Arizona. “When you get to that generation, there was a real distrust of financial institutions,” he said, referring to people old enough to remember the Great Depression and the bank failures of the 1930s.

Mr Criner said if family members notice this behaviour, communication is important. “When this is acknowledged, it is important to start the dialogue,” he said.

What can go wrong?

While throwing money in the trash is a very real risk of keeping money at home, it’s far from the only one, advisers say. Valuables stored in the home can be stolen, destroyed by a disaster such as fire, or secretly misappropriated by a family member.

“Things have a way of disappearing from the home, especially when you have existing family drama or an argument,” said Alvina Lo, chief wealth strategist at Wilmington Trust, a subsidiary of M&T Bank.

This potential for tension among survivors can arise even if no misappropriation occurs, experts say.

“Often, even if there is a well-intentioned adult child living nearby and assets are discovered, there can be a lot of skepticism between siblings,” said Abby Flaum, director and family wealth strategist at Homrich Berg, a wealth management firm in Atlanta. .

People who keep cash at home are missing out on the significant wealth generation that can happen over decades if that money is invested.

“The lost interest — it probably would have been double just if I had kept it in the bank all those years instead of keeping it in the back of the closet,” said Patrick Simasco, a real estate attorney in Mount Clemons, Michigan, who recalls nearly half a million dollars in cash and gold at the home of an elderly client who had hired him to execute her estate.

There are also potential pitfalls when it comes to distributing these assets.

“It’s just messy, it’s informal and it can lead to accounting nightmares,” Mr. Krainer said.

Because the money has no ownership records, “it’s very unclear in terms of the ownership rights of who it belongs to,” Ms. Lo said.

Without a paper trail establishing ownership or a detailed will, determining inheritances can be difficult. “I’ve seen it when you have a second marriage where that can be a problem,” Ms. Lo said, especially since hidden assets are unlikely to be accounted for in a will or estate plan.

Experts also say such unreported values can cause headaches for wealthy families, especially those whose estates are near the threshold for either the federal estate tax or state estate or inheritance taxes.

“If it’s on the borderline, those assets could elevate the estate to a taxable estate,” said Neil Carbone, a trusts and estates attorney and partner at the law firm of Farrell Fritz. (For 2024, the federal estate tax exemption is approximately $13.6 million, meaning estates valued below that level are not subject to taxes; some states have estate taxes or inheritance taxes with lower thresholds .)

Mr Carbone said he advises clients who inherit valuable but illiquid items, such as artwork, to get them appraised. Determining the value of the item at the time the owner died and the heir took ownership can be important, especially if the item in question has become significantly more valuable over the years.

The Internal Revenue Service has a myriad of ways to find potentially taxable wealth, Mr. Carbone said. Auditors can evaluate a homeowner’s insurance policy to look for riders to insure valuables, review previous gift tax returns to establish a paper trail of ownership, or trace purchases of precious metals.

The other challenge in inheriting non-monetary assets is finding a buyer. “It’s the same if you invest in baseball cards or figurines or Hummel brands,” Mr. Simasco said. “If you’re investing in a non-traditional type of investment — not stocks, bonds or mutual funds — you have to find a buyer for them.” That process can take a significant amount of time if the items are particularly esoteric, Mr. Simasco added, recalling a client whose wealth was mostly associated with a collection of antique guitars.

Money Laundering Actions

Wealth management and estate planning professionals say they see hoarding trends most often among people linked to the Great Depression. But memory-robbing medical conditions like dementia and Alzheimer’s can cause a return to decades-old behaviors, such as hoarding money. They can also cause paranoia, which can lead people to hide valuables and try to block relatives from interfering in their financial affairs on their behalf.

“People who experience this mental decline become the least trusting of the people who are closest to them and who are in the best position to advocate for them,” Mr. Krainer said.

“It can be really hard. We did a lot of planning for clients who could tell that mom or dad was starting to slip a little,” Ms. Flaum said. She said she recommends clients in this situation get a financial power of attorney and consider setting up a revocable trust, a financial tool where assets can be held as people age and which allows beneficiaries to avoid probate after death.

“A revocable trust is a really good way to plan for asset management in the event of incapacity,” she said. “You can include provisions about how incapacity to manage those trust assets can be determined.”

Hiding wealth at home has also tended to persist over the years among certain groups of people.

“In particular, minority communities were very distrustful of or had no access to financial institutions, resulting in the proverbial money under the mattress,” Mr Criner said.

“This is because minorities have not had access to these institutions for decades, and even when there was access, there was a lot of abuse,” he said. “They weren’t always treated fairly or treated fairly.”

Those memories linger, Mr. Kreiner said, adding that as a black man he heard those attitudes expressed even in his own family. “This sense of mistrust is passed down from generation to generation. I’ve heard my father talk about it, I’ve heard my grandfather talk about it,” he said.

Ms Lo of the Wilmington Trust said she had similar personal experiences. “A lot of it is also very cultural,” she said. “I’m Asian American and this happens all the time in my community.”

Over time, experts predict that people will keep cash at home will decrease as the collective memory of the Great Depression fades and the use of digital banking continues to increase.

“People tend to do more and more electronic payments for things,” Mr Carbone said.

While this is good news from a financial planning perspective, people who have seen this dynamic play out say it will also save survivors the painful emotions these discoveries can cause.

Finding, for example, hundred dollar bills hidden among items that would normally be donated or thrown away is stressful for surviving loved ones because it requires a much longer, painstaking process of removing personal items from the home. “Families are grieving and it’s very difficult for them,” said Ms. Volpe, who is a real estate broker in Hyde Park, New York.

Despite a decades-long career in real estate, Ms. Volpe said she never expected to find this scenario in her own family. She credited her mother with concluding that there was more money hidden in her grandmother’s books than meets the eye.

“Thank God my mother thinks like that,” she said, admitting, “I would have thrown all those books in the trash.”