“The James Webb Telescope: Are We Alone?” on The Whole Story with Anderson Cooper offers an inside look at the most powerful telescope ever built. The show premieres Sunday, June 16 at 8:00 PM ET/PT on CNN.

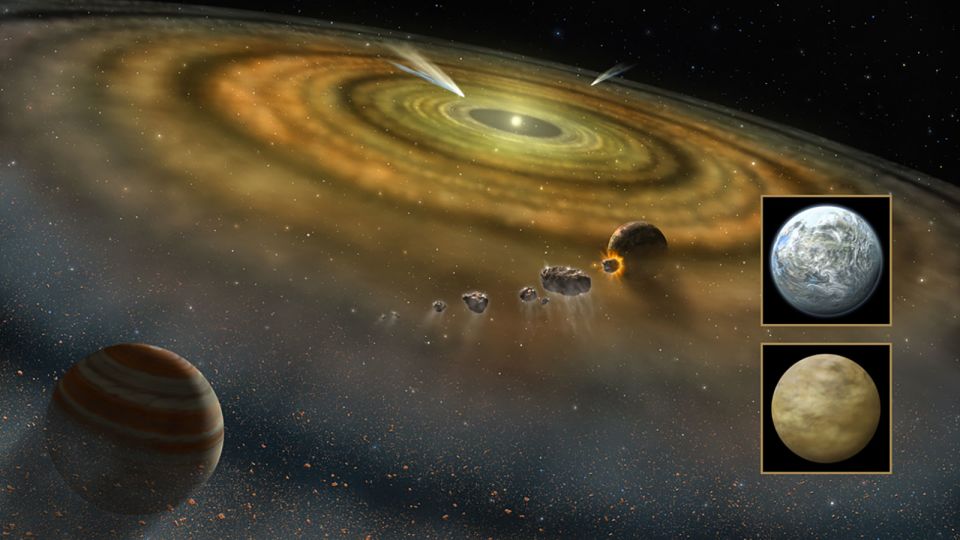

A collision between giant asteroids may have occurred in a neighboring star system called Beta Pictoris in recent years, and two different space observatories are helping to tell the story.

The Beta Pictoris system, located just 63 light-years from Earth, has long intrigued astronomers due to its proximity and age.

While our solar system is estimated to be about 4.5 billion years old, Beta Pictoris is considered a “juvenile planetary system” at 20 million years old, said astronomer Christine Chen, a researcher at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who has observed the system numerous times.

“That means it’s still forming,” she said during a presentation at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Madison, Wis., on June 10. “It’s a partially formed planetary system, but it’s not ready yet.”

Chen observed Beta Pictoris, which has two known gas giant planets called Beta Pictoris b and c, using the now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope in 2004 and 2005. At the time, Chen and her colleagues saw several different populations of dust in the system.

“So I was extremely excited to observe this system again in 2023 using the James Webb Space Telescope,” Chen said. “And I was really hoping to understand the planetary system in much greater detail, and we definitely do.”

Since Webb opened its infrared eye to the universe in 2022, scientists have used the space observatory to peer through gas and dust to study supernovae, exoplanets and distant galaxies.

By comparing the Spitzer and Webb observations, Chen and her colleagues realized that the data they captured 20 years ago happened at a rather random time—and two of the large dust clouds have since disappeared.

Chen is the lead author of a study comparing the observations presented Monday at the conference.

“Most of JWST’s discoveries come from things the telescope has detected directly,” study co-author Cicero Lu, a former Johns Hopkins astrophysics postdoctoral fellow, said in a statement. “In this case, the story is a bit different because our results come from what JWST didn’t see.”

The team believes the Spitzer data suggests that a pair of giant asteroids collided just before the telescope’s observations of the system.

“Beta Pictoris is at an age when planet formation in the terrestrial planet zone is still going on through collisions of giant asteroids, so what we can see here is basically how rocky planets and other bodies are forming in real time,” Chen said.

Evidence of a giant collision

When Chen and her team observed Beta Pictoris between 2004 and 2005, they probably saw evidence of a “collision-active planetary system,” but they just didn’t realize it yet, she said.

In addition to the two known planets, previous research has found evidence of comets and asteroids moving through the young system.

As comets and asteroids collide, they create dusty debris and help form rocky planets.

The collision, which occurred just before Spitzer’s observations, likely pulverized a massive asteroid into fine dust particles that are smaller than pollen or powdered sugar, Chen said.

She said the mass of dust created was about 100,000 times the size of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs, which is estimated to be between 6.2 and 9.3 miles (10 and 15 kilometers) wide. The dust was then pushed out of the planetary system by radiation from the central star, which is slightly hotter than our sun.

Astronomers originally thought that small bodies collided and added to the dust clouds seen in Beta Pictoris over time. But the powerful Webb telescope failed to detect any dust.

Although gas giant planets have formed in the system, rocky planets are likely still forming.

Astronomers expect to make more observations of the system to see if more planets appear. In the meantime, studying the system could help astronomers better understand what the early days of our own solar system looked like.

“The question we’re trying to contextualize is whether this whole process of terrestrial and giant planet formation is common or rare, and the even more fundamental question: Are planetary systems like the Solar System that rare?” said study co-author Kadin Worthen, a doctoral student in astrophysics at Johns Hopkins, in a statement. “We’re basically trying to figure out how weird or average we are.”

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news of fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more.

For more CNN news and bulletins, create an account at CNN.com