A double quasar spiraling towards a major merger has been discovered, illuminating the ‘cosmic dawn’ just 900 million years after the Big Bang.

They are the first quasar a pair spotted so far back in space time.

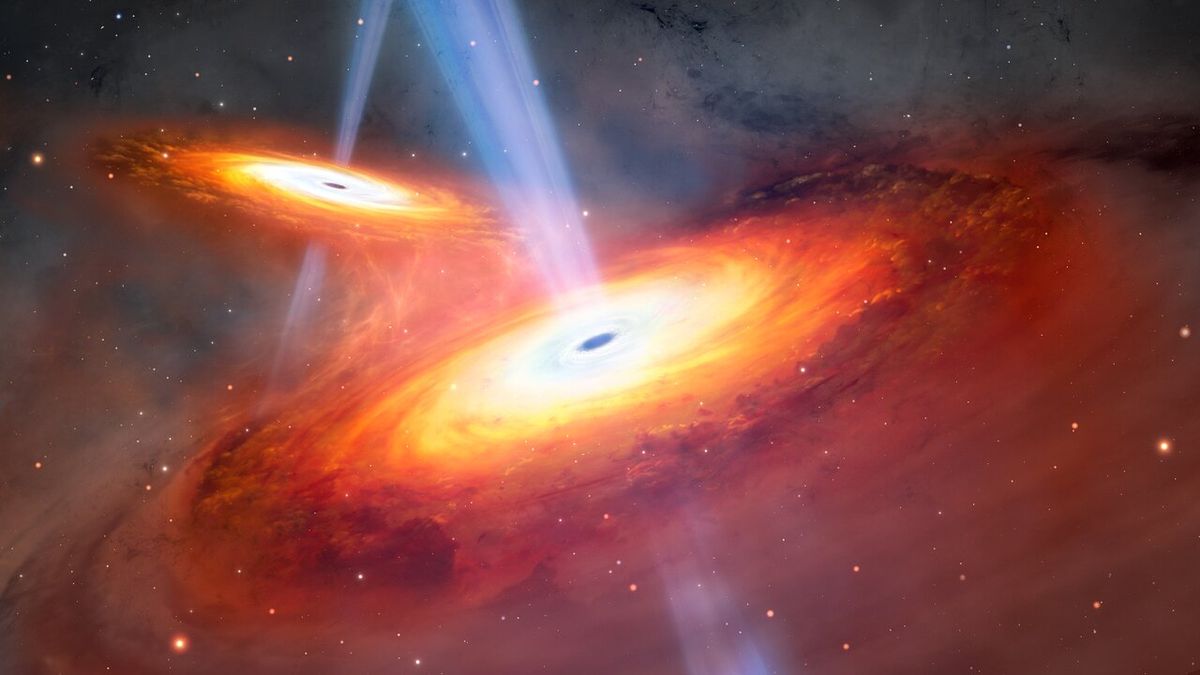

Quasars grow rapidly supermassive black holes in the cores of the hyperactive galaxies. Streams of gas are forced into the throats of black holes and become trapped in the bottleneck of the accretion disk, which is a dense ring of ultrahot gas that queues up to fall into the black hole. Not everything falls; the magnetic fields wrapped around the spinning accretion disk are able to pick up highly charged particles and send them back into deep space in the form of two jets that compete almost at the speed of light. The combination of jets and accretion disk makes the quasar appear intensely luminous, even billions of years away light years.

Because every large galaxy has a monstrous one Black hole like its dark heat, when galaxies collide and merge, so do their supermassive black holes eventually. During the cosmic dawn – which describes the first billion years of cosmic history when stars and galaxies first appeared on the scene – an expanding universe was smaller than it is today, and therefore galaxies were closer together and merged more often. Yet while over 330 single quasars have been spotted so far in the universe’s first billion years, the expected abundant population of binary quasars has been conspicuous by their absence — until now.

The newly discovered binary quasar, J121503.42–014858.7 and J121503.55–014859.3 — called C1 and C2 by their discoverers — was spotted using Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii by a team led by Yoshiki Matsuoka of Ehime University in Japan.

Astronomers tracked spectroscopically using Subaru’s Faint Object Camera and Spectrograph (FOCAS) and the Gemini Near-Infrared Spectrograph (GNIRS) on the Gemini North telescope, also located atop Mauna Kea.

“What we learned from the GNIRS observations was that quasars are too faint to be detected in the near-infrared range, even with one of the largest telescopes on earth,” Matsuoka said in statement.

Traveling 12.9 billion years, the light of the quasars was with redshift and stretched to longer wavelengths by cosmic expansion, so that light that began as X-rays or ultraviolet rays ends up near the red and infrared ends of electromagnetic spectrum. Light from quasars should be detectable in the near-infrared, but the fact that they are weak at this wavelength means that much of their light is actually at other wavelengths, produced by the increased star formation in galaxies , in which the quasars are located.

Connected: The Event Horizon telescope spies jets erupting from a nearby supermassive black hole

Enhanced star formation, which for C1 and C2 is estimated to be between 100 and 550 sun tables per year (compared to one to 10 solar masses per year in ours Milky way galaxy), is a common symptom of merging galaxies, as raw molecular hydrogen gas is stirred up by the interaction and triggered to form new stars.

The two black holes have also moved within 40,000 light-years (12,000 parsecs) of each other. Although this is still a long distance, observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile found a bridge of gas spanning this distance between C1 and C2. The two black holes are already connected, and this connection will become stronger as they continue to approach each other.

The existence of C1 and C2 is further evidence that galaxies and their black holes growing rapidly, and to enormous size and mass, during the cosmic dawn era, challenging our models of how they must have formed. Each of the black holes has a mass of about 100 million times the mass of ours sunwhich is huge; Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy, is tiny compared to a mass of only 4.1 million solar masses. Plus, the host galaxies of C1 and C2 have a combined mass in the region of 90 billion and 50 billion solar masses, respectively, which, while significantly less than the Milky Way, is still huge for the time.

As such, the discovery of this binary quasar and their host galaxies provides a vital data point for better understanding the early universe and especially the reionization epoch, when most of the gas in the universe was ionized by radiation from the first stars , galaxies and quasars ending in cosmic dark ages. One of the great puzzles of cosmology is which of these three things contributed most to reionization.

“The statistical properties of reionization-era quasars tell us many things, such as the progress and origin of reionization, the formation of supermassive black holes during the cosmic dawn, and the earliest evolution of quasar host galaxies,” Matsuoka said.

We see these two quasars as they were about 12.9 billion years ago. What happened to them since then? The simulations show that eventually the two black holes will merge in a burst gravitational waves. This will make the combined quasar even brighter and increase the star formation rate in the merged galaxy to over 1,000 solar masses per year, creating one of the most extreme galaxies in the Universe. He may eventually become one of the giants elliptical galaxies at the heart of a massive galaxy cluster, such as M87 in the Virgo cluster.

The findings were published on April 5 in The Astrophysical Journal Letterswith accompanying paper discussion of ALMA measurements.