Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news of fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more.

CNN

—

Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft was set to celebrate its crowning achievement this month: carrying two NASA astronauts on a round trip to the International Space Station, proving the long-delayed and super-budgeted capsule is up to the task.

The Starliner is halfway to that goal.

But the two veteran astronauts piloting that test flight are now in a precarious position — extending their stay aboard the space station for a second time as engineers on the ground scramble to learn more about the problems that plagued the first leg of their journey.

Spaceflight veterans Sonny Williams and Butch Wilmore arrived at the space station aboard Starliner on June 6. NASA initially predicted their stay would last about a week.

But problems the vehicle experienced along the way, including helium leaks and thrusters that suddenly stopped working, raised questions about how the back half of the mission would play out.

Williams and Wilmore will now return no earlier than June 26, NASA said Tuesday, extending their mission to at least 20 days as engineers race to better understand the spacecraft’s problems while it is safely attached to the space station. station.

Officials said there’s no reason to believe Starliner won’t be able to return astronauts back home, although “we really want to work with the rest of the data,” said Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, in Tuesday press conference.

Meanwhile, Boeing tried to portray the mission as a success and a learning opportunity, albeit one that left the Starliner team struggling with the “unplanned” side of the mission, as Mark Nappi, Boeing vice president and program manager of the Starliner program, put it in Tuesday.

It’s not uncommon for astronauts to unexpectedly extend their stay aboard the space station—by days, weeks, or even months. (NASA also said the Starliner could spend up to 45 days at the orbiting lab if needed, according to Stich.)

But the situation creates a moment of uncertainty and embarrassment that joins the long list of similar missteps by the Boeing Starliner program, which is already years behind schedule. It also adds to a chorus of unfavorable news that has followed Boeing as a company for some time.

Boeing and NASA engineers said they decided to keep the Starliner — and with it Williams and Wilmore — aboard the station longer than expected, primarily to conduct additional analysis. Helium leaks and problems with the thrusters occurred in a part of the vehicle that was not designed to survive the journey from space, so mission teams are delaying the spacecraft’s return as part of a last-ditch effort to learn all they can about the which has gone wrong.

Danger looms every time a spacecraft returns home from orbit. This is perhaps the most dangerous part of any mission in space.

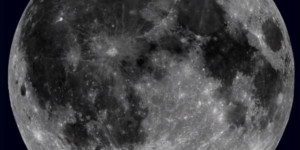

NASA

NASA’s Boeing Crew Flight Test Starliner spacecraft is pictured docked to the front port of the Harmony module on June 13 as the International Space Station orbits 262 miles above the Mediterranean coast of Egypt.

The journey would require the Starliner to hit Earth’s thick atmosphere while traveling at 22 times the speed of sound. The process will bake the exterior of the spacecraft at approximately 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Then a set of parachutes — which Boeing redesigned and tested as recently as January — must safely slow the capsule down before it reaches the ground. (The Starliner will be the first U.S.-built capsule to parachute to land instead of splashing in the ocean. Boeing hopes this approach will make it easier to restore and refurbish the Starliner after flight.)

Starliner’s journey to this historic crewed test mission began in 2014, when NASA enlisted Boeing and SpaceX to develop a spacecraft capable of carrying astronauts to the International Space Station.

At the time, Boeing was seen as the hard-nosed aerospace giant likely to get the job done first, while SpaceX was the unpredictable newcomer.

In the past decade, however, the tides have turned.

SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft successfully completed its first crewed mission—which appears to have gone off without a hitch—in 2020. And since then, the vehicle has regularly flown astronauts and paying customers.

Joel Kowsky/NASA

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying the company’s Crew Dragon spacecraft launched NASA astronauts Robert Behnken and Douglas Hurley to the International Space Station, marking the spacecraft’s first crewed flight on May 30, 2020.

The two astronauts who piloted Crew Dragon’s inaugural flight — Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley — also stayed aboard the space station longer than expected, clocking in at more than 60 days, rather than the short stays expected on such test flights.

But Hurley and Behnken’s stay was extended so the astronauts could help with daily activities aboard the space station, which was understaffed at the time. The extension does not directly address specific software or hardware issues with SpaceX’s Crew Dragon.

Spacecraft problems, on the other hand, have dogged Boeing’s Starliner program virtually every step of the way. The vehicle has faced years of delays, setbacks and additional costs that have cost the company more than $1 billion, according to public financial records.

Starliner’s first uncrewed test mission in late 2019 was full of missteps. The vehicle failed to ignite in orbit, a symptom of software problems involving a coding error that set the internal clock by 11 o’clock.

A second uncrewed flight in 2022 revealed additional software issues and issues with some of the vehicle’s thrusters.

Stitch, NASA’s program manager, indicated during a June 6 news conference that engineers may not have fully resolved these issues as of 2022.

“We thought we had solved that problem,” Stich said, adding, “I think we’re missing something fundamental that’s going on inside the thruster.”

Michael Lembeck, an associate professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who was a consultant for Boeing’s space flight division from 2009 to 2014, told CNN it would be difficult to determine whether additional ground tests could to have caught the problems with the thrusters at hand.

But Lembeck emphasized that assessing the success of this test mission is not as simple as directly comparing it to SpaceX’s inaugural Crew Dragon crewed test flight.

For example, he said, SpaceX’s Dragon cargo capsule — Crew Dragon’s directorial predecessor — completed more than a decade of uncrewed cargo missions to the space station before Crew Dragon flew.

“SpaceX had a lead in the cargo program,” Lembeck said. “I think they have an advantage that Boeing didn’t have. Boeing has to build a crew vehicle from scratch.”

If this Starliner test mission encounters further setbacks, however, it could put Boeing in a situation where it must rely on its rival to bring Williams and Wilmore home.

“The disturbing backup is that Crew Dragon will have to go and pick up the astronauts,” Lembeck said. The spacecraft “could be sent up with two crew members and returned with four — and that would probably be the way home.”

Boeing executives have repeatedly sought to make clear that the Starliner program operates independently of the company’s other units — including the commercial jet division, which has been at the center of scandals for years.

“We have people flying this vehicle. We always take this so seriously,” Nappi said during a news briefing in April before the Starliner took off.

Nappi also announced at the time that the Starliner crew was operating at “peak performance” and was “really looking forward to completing” a safe mission.

Asked about that claim Tuesday, Stich, NASA’s executive director, said Boeing and NASA officials always expected to find additional problems to be resolved during this test flight.

Williams hinted at that expectation during a press conference before the flight, saying, “We’re always finding things and we’re always going to keep finding things.

“Not everything is going to be absolutely perfect while we’re flying the spacecraft. … We feel very secure and comfortable with how this spacecraft is flying, and we have backup procedures in place in case we need them,” Williams said.

However, Stitch acknowledged Tuesday that Boeing and NASA may have been able to prevent some of the disruptions the Starliner faced: “Maybe we could have done different tests on the ground to characterize some of the (thruster problems) before time,” he said.