B-36 Peacemaker mechanic

In response to the US Army Air Force’s requirement for a strategic bomber with intercontinental range, Consolidated Vultee (later Convair) designed the B-36 during World War II. The aircraft made its first flight in August 1946, and in June 1948 the Strategic Air Command received its first operational B-36.

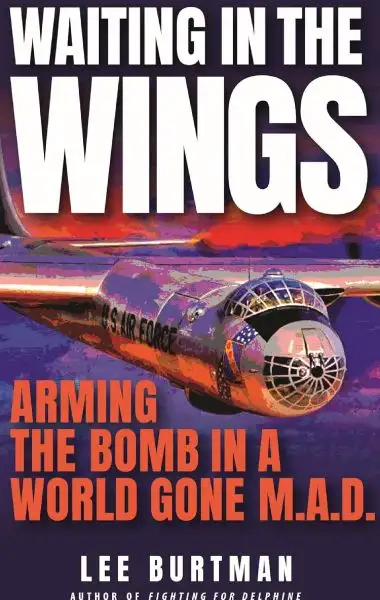

As Lee Burtman explains in his book Waiting in the Wings: Arming the Bomb in a World Gone MAD, as the largest combat aircraft ever built, the B-36 fulfilled a crucial nuclear deterrence role as part of SAC. Her father, Neil, was in charge of maintaining the plane even in flight. In fact, much attention is paid to the fact that the wing of the B-36 is deep enough to allow engineers to get into it and maintain the engines in flight.

Neil felt honored to be chosen to fly the Peacemaker, but the assignment was definitely no walk in the park! His typical route was called “milk”, where minimal resistance from the enemy was expected. After gassing up in Rapid City, the team flew to Maine. If all systems check out, the plane makes a rough circuit from Newfoundland to Greenland, through Norway and Sweden, through Russia and North Africa, and then back across the Atlantic. Neal wasn’t even sure where they were half the time!

These simulated bombings lasted fourteen to forty hours, an average of thirty-two hours during the week. Neil exclaimed that even after overcoming his initial fear of flying and flying for a few months, the tense initial hours in the air still “scared the hair out!” Despite his excellent care of the aircraft, inherent system malfunctions could bring it down, if not we’re talking about the Soviet MiGs circling below.

Unnerving sound

Just the sound of the bomber was unnerving. A distinctive undulating drone created by her engines running at their highest revs passed through his lungs and stomach. He could feel the reverberations throughout his body long after he returned to earth. It was so loud that Neal couldn’t hear anything else and his ears were ringing for hours and hours after the flight. The people of the earth knew she was approaching from ten miles away, and their houses and windows would rattle wildly to announce her arrival.

The throbbing vibrations of the plane felt and sounded like they would tear his body apart. It really looked like they would—Neil could see daylight as the ‘skin’ and ‘ribs’ were torn apart, then clashed again at the seams like an accordion playing. After each flight, sheet metal workers spent hours repairing the “skin” and fixing the popped rivets.

Constant voltage; gas fumes; lack of food, sleep and nicotine; and three days of intense convulsions on the plane forced Neal and his friends to throw up violently on the tarmac shortly after landing. He hated the shorter weekend flights, when the crew might have only three or four hours on the ground to refuel and acclimatize. To prevent the engines from freezing, the men had to get back into the blue before their stomachs were settled.

F-1 electrically heated suit

Even after spending many cold Minnesota winters as a child, playing in the snow for hours wearing a thin jacket and wet gloves, Neal was unprepared for the bitter cold of the stratosphere. In some parts of the plane where he worked, it could be twenty to thirty below zero. In contrast, the bunk bed in the rear compartment can be ninety degrees above and twenty degrees in the lower bunk, making it impossible to sleep on either level. It was so uncomfortable that Neal slept very little in bed—napping or reading where he could, sitting or even standing.

Neal was outfitted with an electrically heated F-1 suit, included in the aircraft. Unfortunately, this barely stopped one from freezing to death. He wore gloves, boots, an oxygen mask, a heated high-altitude flight helmet with earplugs and a headset to keep in touch with the cockpit. Most importantly, he was wearing a parachute and a “Mae West” on his chest (a life jacket named after the beautiful, risk-taking vaudeville, theater and film actress).

A small galley contained two mini-stoves, but there was rarely time or motivation to cook anything. Typical meals consisted of sandwiches in self-heating wraps or C or K rations. Rations usually included some kind of meat (spam anyone?), powdered eggs, cheese and crackers, preserved purple plums, chocolate bars, instant coffee, and chewing gum (plus a toilet paper and cigarettes).

The use of toilet paper was particularly problematic. It was often too cold to use the “head” so one could either wear a diaper, which Neal adamantly refused to do, or use a “pee tube” that emptied into a plastic bag. Neil admitted that he was too scared during the flight to try to eliminate anything else!

The tunnel

He could not use cigarettes either, as smoking with splashing gas and smoke penetrating the air was strictly prohibited. Neil had been a heavy smoker since his teenage years and the nicotine withdrawal he experienced every time he flew was debilitating.

The first day without cigarettes made him feel anxious, restless, dizzy and irritable and gave him a severe headache. The second day brought insomnia, trouble concentrating, and a drop in blood sugar, creating sudden hunger and cravings for sweets and carbs. Unfortunately, the pathetic Air Force snacks did not fully satisfy him. By the third day, the withdrawal symptoms were at their peak. Just when he couldn’t take it a second longer, he greedily grabbed a saved cigarette from his pocket and took a deep breath – after landing and purging.

On these flights, Neil starts at the front of the plane for a briefing with the bombardier responsible for directing the aerial bombs. He then talks to the navigator, who guides the plane using radar, charts and maps. He then headed to the rear, accessed through a pressurized tunnel called the “train”. The tunnel, measuring about thirty inches in diameter and eighty-seven feet long, ran past the fuselage and through the bomb bay. Neal would move his parachute to his chest, then lay on his back on a flat sled attached to the monorail. After grabbing an overhead cable, he stubbornly pulled himself up through the tunnel by hand, no easy feat while carrying all his bulky gear.

A B-36 mechanic’s critical job: keeping the engines cool and the carburetors warm

Sometimes the pilots had a bit of fun with the rear crew – a slight pitch of the plane’s nose down made the men groan and work even harder to maneuver through the tunnel. If they tilted the nose up, the screams of the crew members as they descended backwards at breakneck speed were good for a laugh.

Neil’s first task was to crawl into the wings of the plane to work on the engines in flight. The huge wings were over seven feet thick at their base (where they attached to the fuselage) and tapered towards the tips. While securely strapped in, Neal could check the fuel tanks and landing gear, monitor the engines with an analyzer, check intercooler settings and gear movements, and reset blown circuit breakers on the electrical panel.

Important work was keeping the engines cool and the carburettors warm. The stainless steel protective walls surrounding the engines sometimes cracked, overheating the cylinders and causing fires. The airframe is made of a highly flammable metal, magnesium, creating a dangerous combination. Three B-36s were lost to in-flight fires—one was even carrying an atomic bomb that, fortunately, had not yet been activated.

The least of B-36 mechanics’ worries

The engines were leaking oil, which had to be constantly cleaned and topped up. At times the supply to the 150 gallon engine was insufficient so it had to be shut down. Neil also completed the terrifying task of replacing hundreds of spark plugs in the engine block. Each of the six engines had 56 spark plugs and all 336 required frequent replacement as the lead avgs continually fouled them while the aircraft was at cruising speed.

Besides inhaling the ever-present toxic fumes, Neal often had direct contact with the fuel as leaks in the injection lines sprayed it. Also, after being bent for several hours, the fuel tanks in the wings dislodged the joint seals, allowing purple fuel to drip all over Neal. Also, when the plane does a ‘gun’ roll, turning quickly and sharply through 60 degrees, the gas will escape, dousing Neal with more poisonous liquid. Over the course of multiple trips, Neal probably received more than his share of lead and other chemicals. However, such exposure would prove to be the least of his worries.

Waiting for the wings

Lee Burtman was born and raised in Minneapolis, Minnesota (USA) and lives in the northern suburbs with her husband Greg and son Kyle. They also enjoy three other grown children, their spouses and eight grandchildren.

Lee is a retired educator with a passion for telling the stories no one else is telling—the true experiences of little-known, ordinary soldiers and airmen who put their lives on the line to ensure our freedom.

Waiting in the Wings: Arming the Bomb in a World Gone MAD is her third book and highlights her father Neil’s work in the B-36 Peacemaker. It is available through the author by writing to burtmanlee@gmail.com or Amazon–Waiting in the Wings by Lee Burtman.

Photo credit: Lt. Col. Frank F. Kleinwechter / US Air Force