The heat cured the infection within a few weeks, and about 70 percent of the infected frogs survived the 15-week experiment, said lead researcher Anthony Waddle. Waddell and a team of biologists published the results last week in Nature magazine, hoping that their simple invention will help solve a huge wildlife problem.

Waddell built the shelters using black bricks and greenhouse netting.

“It’s going to be bitterly cold outside, but once you get inside [the shelter] … I would just sweat profusely because of the humidity and the heat,” Waddle, a postdoctoral fellow at Macquarie University in Macquarie Park, Australia, told The Washington Post.

Chytridiomycosis, which originates from Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, an aquatic mushroom, was thought to have been first discovered in Asia in the 1930s before trade and travel saw it spread rapidly around the world. The infectious fungus, which has brought dozens of amphibian species to the brink of extinction, causes breathing problems while many amphibians’ hearts stop.

Scientists have tried to spare the amphibians by removing infected species from their habitats, chemically disinfecting their homes and warming their water sources to fight the fungus. In 2021, Waddle created a frog vaccine against Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. However, he wanted to invent a solution that the frogs could use themselves, especially in the winter when cases of chytridiomycosis are at their highest.

In December 2020, Waddell placed several green and gold bell frogs, which are endangered in the Australian state of New South Wales, near a metal fence post that was cold on one side and hot on the other. Frogs gravitated to the warm side.

The researchers then divided 66 infected frogs between warm and cold areas in their laboratory. Frogs in the warm zone, which was about 86 degrees, fought off the infection, while those in the cold zone, which was about 66 degrees, remained infected.

These results led the researchers to believe that the frogs would choose—and benefit from—living in a warm habitat if the researchers created one.

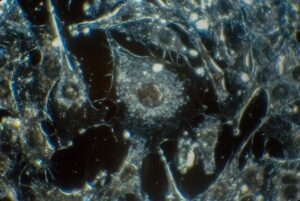

Scientists use their hardware supplies for the basic experiment: clay bricks, black paint, greenhouse netting, and cable ties. They painted the bricks black to attract the heat from the sun. Then they arranged 10 bricks, each with 10 small holes, one on top of the other. They covered multiple stacks of bricks with greenhouse netting to retain heat, and cable ties stabilized the shelters.

“I didn’t think it would work because of its simplicity,” Waddle said.

At Macquarie University’s campus in July 2021, researchers placed the shelters in tubs of gravel, water, artificial plants and pots to mimic the frogs’ typical habitats. 239 frogs were then placed in the tubs and given a choice between an unshaded shelter or a towel-shaded one. Most gravitated to the warmth of the bricks in the unshaded shelters.

Unshaded shelters were about eight degrees warmer than shaded habitats, and that mattered. About a month after the experiment began, the researchers swabbed the frogs’ skin and found that the infection healed most quickly in frogs in unshaded shelters.

By November 2021 — just before summer began in Australia — 167 of the 239 frogs were still alive, Waddle said. Wild frogs usually begin to die about three weeks after being infected, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

The researchers also found that frogs that survived chytridiomycosis became more resistant to the disease — a promising sign for the survival of the species, which can live about 15 years in captivity.

Bryan Pijanowski, a professor of forestry and natural resources at Purdue University, said in an email to The Post that the shelters built by Waddle offer “some optimism” about solving a disease that has wiped out at least 90 species of amphibians.

“These are scary numbers that require new approaches to turn the tide,” he said.

Waddell has established several shelters in Sydney’s Olympic Park, Australia, home to one of the largest remaining populations of green and gold frogs. He plans to monitor the population over the next few years.

He said he it is hoped that parks and homeowners will implement their own “frog saunas.” He created a public guide to building them, estimating that they cost about $80 each.

“Conservation research is a lot of waste,” Waddell said. “You just try things, they don’t work. You try things, they don’t work. But we have something, and it’s something we can deliver immediately.”