The search for the “missing matter” in the universe has failed so many times that some exotic proposals are taken more seriously than they once were. As Sherlock Holmes said, “When you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains incredible must be the truth.” In this case, there are many incredible ideas that are tested to see if they are impossible. One that has attracted enough attention that IFLScience was asked to discuss it is Dyson Spheres. There are good reasons to conclude that these hypothetical realms are not the question you are looking for, but also to examine how we know this.

First, what is a Dyson sphere?

Only a small part of the Sun’s energy falls on its planets, and the rest goes out into space. In 1937, science fiction writer Olaf Stapledon wrote a book, The star maker, which explores the ideas of much more advanced civilizations’ pursuit of energy. The book inspired physicist Freeman Dyson to propose that such civilizations build giant thin surfaces in space to capture more of their stars’ energy, eventually partially or completely surrounding the star.

Dyson noted that such structures would block visible light from the star to observers elsewhere, but would emit infrared light. Therefore, he argues, a way to find advanced extraterrestrial civilizations may be to search for spectra dominated by infrared rays.

The idea captured the imagination of many people and achieved a surge in popularity when the mystery of KIC 8462852 (also known as Boyajian’s Star) emerged in 2015. KIC 8462852 undergoes significant dips in brightness at irregular intervals too large to be the result of planets blocking its light. There was so much speculation that the observed behavior might be caused by a partially constructed Dyson Sphere that another nickname, the “Alien Megastructure Star”, became common.

What is the missing mass?

There are actually two types of mass that our surveys of the local universe have failed to detect. The better known of these is dark matter, the mass needed to explain the motions of galaxies according to the laws of gravity. The other kind of missing mass is more ordinary material, probably mostly composed of hydrogen and helium, as opposed to dark matter, which is most likely exotic particles.

When astronomers talk about “missing mass,” they mean the second kind. We know that this category is made up of regular elements because evidence from shortly after the birth of the universe allows us to calculate how much ordinary matter there must be in the universe today. When we look around us, we can only see about two-thirds of that amount.

This category lacks much less mass than dark matter, but it’s still an awful lot. Among the explanations are vast filaments of gas stretching between galaxies

So can Dyson Spheres account for one of two types of missing mass?

Unfortunately, almost certainly not.

After people realized how cool Dyson Spheres would be and entertained the potential sci-fi ideas of living inside something so mind-bogglingly huge, physicists considered the practicalities. And it turns out that full Dyson Spheres just don’t make sense.

The material for the Dyson Sphere has to come from somewhere. It is very unlikely that even the most advanced civilization would be able to take matter from its star and turn it into something solid. If they could, they probably wouldn’t rely on star power anyway. Therefore, the material of the Sphere must be made of planets, moons and asteroids.

Some star systems have more mass in orbit than ours, others probably less. But there’s no reason to think we’re unusually light in this department.

This means that there won’t be that much mass in the sphere itself, even if you use every scrap of solid material in the planetary system. If the question was meant to mean “Could the material in the Dyson Spheres be so massive that it accounts for much of the missing matter?” then you’d have to explain where that question came from in the first place. Scouring interstellar space and finding rogue planets or other sources of material to turn into support for solar panels is unlikely to be practical.

The other way to interpret the question is: “Is it possible that there are billions of stars surrounded by Dyson spheres that capture all their light so that we cannot see them, thus making the galaxy much more densely packed with stars than we think?” That’s what people usually mean.

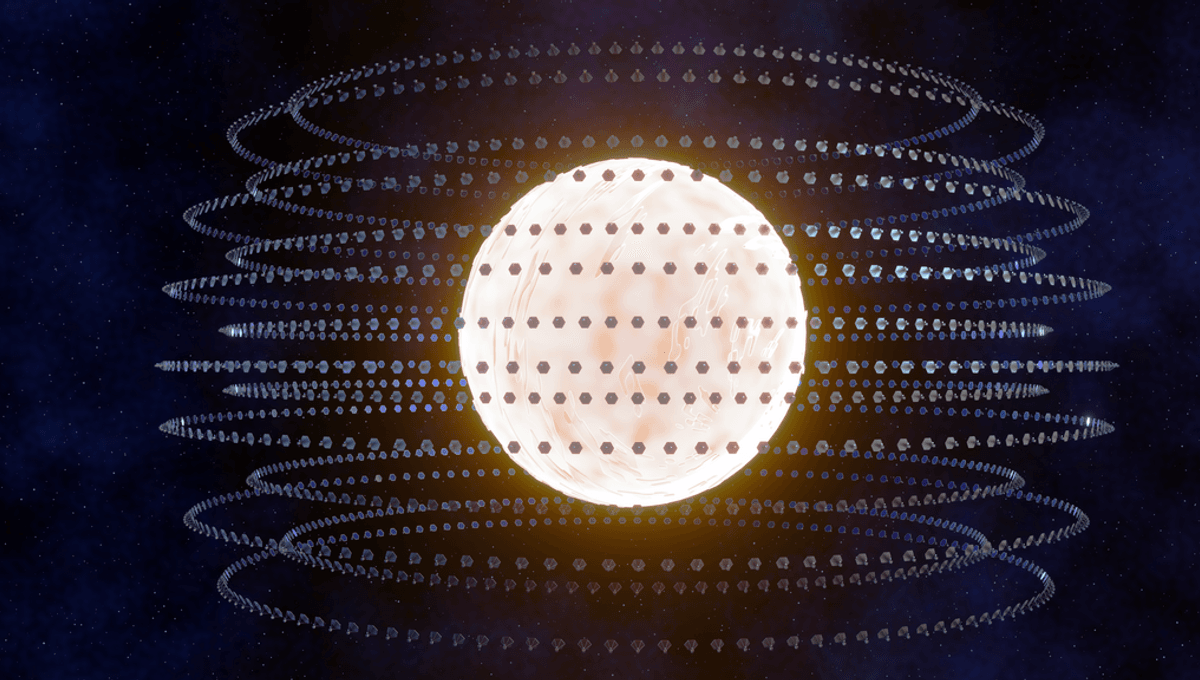

The popular, but almost certainly incorrect, view of the Dyson sphere is one that builds steadily until the star is surrounded by a complete sphere.

However, given the amount of solid material in the Solar System, any fully enclosing Sphere must be very thin. So thin, in fact, that it would be gravitationally unstable. The only way to avoid disaster would be to use massive amounts of energy, making the whole idea a pure waste.

If Dyson spheres exist at all, they are very incomplete, or thin “Dyson rings,” or networks of spots collecting a few percent or less of the star’s light. These are sometimes called Dyson Swarms.

If a star were orbiting Dyson’s swarm, we would see it dimmed by occasional flares as the part came between us and it—the hypothetical situation that made KIC 8462852 famous. Dozens of stars have been identified where this could happen, although other explanations are more likely.

In a case like this, the star will not disappear for an extended period of time. Therefore, our estimates of the number of stars in the galaxy would not be very much in error, if at all. Any small deficient number may be responsible for only a small fraction of the missing matter.

Even if a complete Dyson Sphere is built, an essential feature of the concept is that it will emit in the infrared range. Dyson wanted us to be on the lookout for this kind of infrared signal. JWST and our few other infrared telescopes can’t search everywhere, so they may have missed a few such radiators. However, if they were common enough to solve the mystery of the missing mass, we should have seen them by now.