Getty Images

One of the most widely used network protocols is vulnerable to a newly discovered attack that could allow adversaries to gain control over a range of environments, including industrial controllers, telecommunications services, ISPs and any type of enterprise network.

Short for Remote Authentication Dial-In User Service, RADIUS harkens back to the days of dial-in Internet and network access via public switched telephone networks. Since then, it has remained the de facto standard for lightweight authentication and is supported in nearly all switches, routers, access points, and VPN hubs shipped over the past two decades. Despite its early origins, RADIUS remains an essential element for managing client-server interactions for:

- VPN access

- DSL and Fiber to the Home connections offered by ISPs,

- Wi-Fi and 802.1X authentication

- 2G and 3G cellular roaming

- 5G Data Network Name Authentication

- Offloading mobile data

- Authentication through private APNs to connect mobile devices to corporate networks

- Authentication of critical infrastructure management devices

- Eduroam and OpenRoaming Wi-Fi

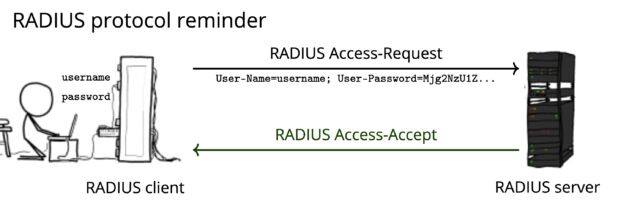

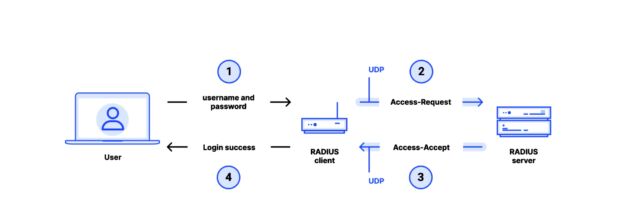

RADIUS provides a seamless interaction between clients—typically routers, switches, or other devices providing network access—and a central RADIUS server that acts as the custodian of user authentication and access policies. The purpose of RADIUS is to provide centralized authentication, authorization, and accounting management for remote logins.

The protocol was developed in 1991 by a company known as Livingston Enterprises. In 1997, the Internet Engineering Task Force made it an official standard, which was updated three years later. Although there is a draft proposal for sending RADIUS traffic inside a TLS-encrypted session that is supported by some vendors, many devices using the protocol only send clear-text packets over UDP (User Datagram Protocol).

XKCD

Goldberg et al.

Native MD5 authentication? Really?

Since 1994, RADIUS has relied on an improvised, homemade use of the MD5 hash function. First created in 1991 and adopted by the IETF in 1992, MD5 was at the time a popular hash function for creating what are known as “message digests” that map arbitrary input such as number, text, or binary file to file with fixed length 16-byte output.

For a cryptographic hash function, it should be computationally impossible for an attacker to find two inputs that map to the same output. Unfortunately, MD5 turned out to be based on a weak design: within a few years there were signs that the feature might be more susceptible than originally thought to attacker-induced collisions, a fatal flaw that allows an attacker to generate two different inputs that produce identical outputs. These suspicions were formally confirmed in a paper published in 2004 by researchers Xiaoyun Wang and Hongbo Yu and further refined in a research paper published three years later.

The latest paper, published in 2007 by researchers Mark Stevens, Arjen Lenstra and Ben de Weger, describes what is known as a chosen-prefix collision, a type of collision that results from two messages chosen by an attacker that, when combined with two additional messages, create the same hash. This means that the adversary freely chooses two different input prefixes 𝑃 and 𝑃’ of arbitrary content, which, when combined with carefully matched suffixes 𝑆 and 𝑆’, which look like random gibberish, generate the same hash. In mathematical notation, such a collision with a chosen prefix would be written as 𝐻(𝑃‖𝑆)=𝐻(𝑃′‖𝑆′). This type of collision attack is much more powerful because it allows the attacker the freedom to create highly customized fakes.

To illustrate the practicality and devastating effects of the attack, Stevens, Lenstra, and de Weger used it to create two cryptographic X.509 certificates that generated the same MD5 signature but different public keys and different distinguished name fields. Such a collision could cause a CA intending to sign a certificate for one domain to unknowingly sign a certificate for an entirely different, malicious domain.

In 2008, a team of researchers including Stevens, Lenstra, and de Weger demonstrated how a chosen prefix attack against MD5 allowed them to create a fake certificate authority that could generate TLS certificates that would be trusted by all major browsers. A key ingredient to the attack is software called hashclash developed by the researchers. Since then, Hashclash has been publicly available.

Despite the undisputed demise of MD5, the feature remained widely used for years. The retirement of MD5 did not begin in earnest until 2012, after malware known as Flame, jointly developed by the Israeli and US governments, was found to have used a chosen-prefix attack to spoof MD5-based code signing by the mechanism for Microsoft Windows Update. Flame uses collision-enabled spoofing to hijack the update mechanism so that the malware can spread from device to device on an infected network.

More than 12 years after Flame’s devastating damage was discovered, and two decades after its collision susceptibility was confirmed, MD5 has brought down another widespread technology that defied the common wisdom to move away from the hashing scheme—the RADIUS protocol, which is supported by hardware or software provided by at least 86 different vendors. The result is “Blast RADIUS,” a sophisticated attack that allows an attacker with an active adversary in the middle to gain administrative access to devices that use RADIUS to authenticate to a server.

“Surprisingly, in the two decades since Wang et al. demonstrated an MD5 hash collision in 2004, RADIUS has not been updated to remove MD5,” the research team behind Blast RADIUS wrote in a paper published Tuesday titled RADIUS/UDP is considered malicious. “In fact, RADIUS appears to have received remarkably little security analysis given its ubiquity in modern networks.”

The paper’s publication is coordinated with security bulletins from at least 90 vendors whose products are vulnerable. Many of the bulletins are accompanied by patches that apply short-term fixes while a working group of industry engineers drafts long-term solutions. Anyone using hardware or software that includes RADIUS should read the technical details provided later in this publication and consult the manufacturer for security guidelines.