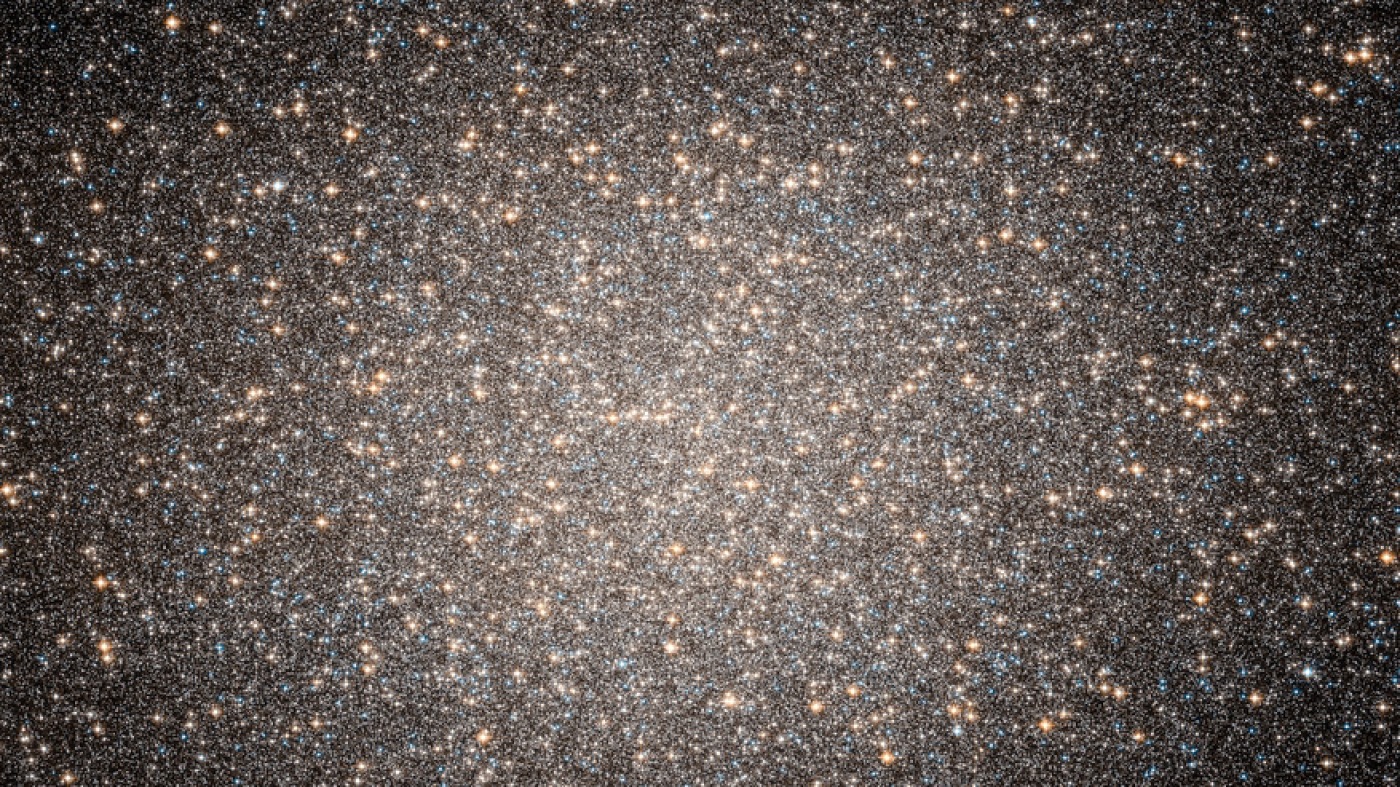

The Omega Centauri star cluster contains millions of stars. The motion of some stars suggests that a medium-sized black hole resides at their center.

NASA/ESA/STScI/AURA

hide caption

caption toggle

NASA/ESA/STScI/AURA

Astronomers have used the Hubble Space Telescope to find evidence of an elusive type of black hole that is about 8,000 times more massive than our sun.

What makes this black hole special is its size, according to a report on the discovery in the journal Nature.

It is much more massive than a garden black hole, the type that is created when a dead star collapses in on itself. But it’s also not as big as the supermassive black hole that lurks at the center of galaxies and can hold anywhere from hundreds of thousands to millions of suns.

Scientists have long been on the hunt for medium-sized black holes like this new one, because finding them could shed light on the myriad ways black holes can form and why some grow into massive monsters.

Despite much effort over the years, however, scientists have had no luck finding solid examples of black holes in the so-called intermediate size, which includes any black hole that is between 100 and 100,000 times the mass of the sun.

“So people wondered if it’s hard to find them because they’re just not there, or because it’s hard to find them?” says Maximilian Haberle of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany.

He and some colleagues recently decided to look for one in a large, bright star cluster known as Omega Centauri. This tightly packed, spherical cloud of millions of stars is about 17,000 light-years across.

Black holes cannot be observed directly because their gravity attracts everything, including light. But researchers can see if a black hole’s gravity affects nearby objects, including stars.

And the researchers knew that the stars in this particular cluster were being monitored continuously by the Hubble Space Telescope, which takes pictures of the cluster’s central region every year.

“This is actually for technical reasons, to calibrate the instruments,” Haberle says.

Because the telescope has taken high-quality observations for more than two decades, Haberle and his colleagues were able to precisely measure the motions of the cluster’s 1.4 million stars.

“Our list of stars for which we have measured motion is much, much larger than any previous effort,” he says, adding that the stars “are all moving in random directions and like a swarm of insects.”

In the end, the researchers were able to pick out seven stars in the center that move much faster than the others. These stars are actually moving so fast that they really should just fly out of the star cluster and disappear forever.

The fact that they remain stuck and concentrated in the center, says Haberle, “means there must be something pulling them gravitationally so they don’t escape. And the only object that could be that massive is an intermediate-mass black hole with a minimum mass of at least 8,000 solar masses.

A black hole is unlikely to be larger than about 50,000 times the mass of the sun, he says, because if it were, scientists would expect many more stars to be affected by its gravity.

He notes that there was a previous claim of finding an intermediate-sized black hole candidate in this cluster dating back to 2008, but this was disputed.

This time, he says, “I think our evidence is very robust” because of the additional years of data.

What’s more, future observations with the James Webb Space Telescope are already planned, and this powerful telescope will be able to look for telltale signs of gas heating up as it falls into the black hole.

“This is really exciting, isn’t it? This is only the second black hole where you can see individual stars moving around the black hole,” said Jenny Green, an astrophysicist at Princeton University.

She notes that the only such observation is the Nobel Prize-winning work that saw stars flying around the black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy, a supermassive that is about four million times more massive than our sun.

“So I think it’s a really big deal. And it’s a much lower-mass black hole,” she says.

No one knows how a black hole of this size is created.

One possibility is that the small black holes merge into a larger one. Evidence for this comes from the detection of gravitational waves from the collision of two black holes, an event that produced a black hole about 150 times more massive than the sun.

Another possible way to grow medium-sized black holes, recently suggested by astronomers, is that many stars could collide into a dense cluster like Omega Centauri and become one very massive star. Later, this large star will collapse into a medium-sized black hole.

Understanding where medium-sized black holes are located and how they grow can help scientists understand what role they may play in the evolution of the even larger ones found at the heart of galaxies.

The newly discovered black hole “is really going to give us important information about how these large black holes formed and grew in the first place,” Green says.

Such supermassive black holes appear to have appeared surprisingly soon after the beginning of the universe, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

That’s according to new observations made with the James Webb Space Telescope, which have astronomers puzzling over how a black hole can get so big so quickly.

Before these observations, Green says, she thought galaxies first grew and then black holes formed at their centers. “I’m not so sure now,” she says. “There is now some tantalizing evidence that black holes grew earlier than their galaxies.”

The medium-sized black holes that exist today may be relics left over from that early black hole creation process, Green says, and could provide clues about how it happened.

“Ultimately, to get the full picture, we need more than one,” she says, “but this really opens the door.”