K. Marsicano

Gaiasia jennyae, a newly discovered freshwater apex predator with a body length of up to 4.5 meters, lurking in swamps and lakes about 280 million years ago. Its broad, flattened head had powerful jaws filled with enormous teeth, ready to capture any prey unlucky enough to swim past it.

The problem is, as far as we know, it shouldn’t have been that big, it should have disappeared tens of millions of years before the time it apparently lived in, and it shouldn’t have been found in northern Namibia. “Gaiasia is the first really good look we’ve had at a completely different ecosystem that we didn’t expect to find,” says Jason Pardo, a postdoctoral fellow at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Pardo co-authored a study on Gaiasia jennyae a finding recently published in Nature.

Common ancestry

“Tetrapods are the animals that crawled out of the water about 380 million years ago, maybe a little earlier,” explains Pardo. These ancient creatures, also known as stem tetrapods, were the common ancestors of modern reptiles, amphibians, mammals and birds. “These animals lived until what we call the end of the Carboniferous, about 370-300 million years ago. A few made it through and they lasted longer, but most of them disappeared about 370 million ago,” he adds.

That is why the discovery of Gaiasia jennyae in Namibian rocks 280 million years old was so surprising. Not only did it not disappear when the rocks in which it was found were laid down, but it dominated its ecosystem as an apex predator. By today’s standards, it was like stumbling upon a secluded island with animals that should have been dead for 70 million years, like a living, breathing T-rex.

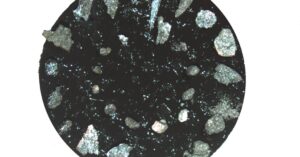

“The skull of gaiasia we found is about 67 centimeters long. We also have a front end of the upper body. We know it was at least 2.5 meters long, probably 3.5, 4.5 meters — a big head and a long salamander-like body,” says Pardo. He said this to Ars gaiasia was a suction feeder: it opened its jaws underwater, which created a vacuum that sucked its prey straight. But the large, interlocking teeth reveal that a powerful bite was also one of its weapons, probably used to hunt larger animals. “We suspect gaiasia fed on bony fish, freshwater sharks, and perhaps even other, smaller ones gaiasia,” Pardo says, suggesting it was a fairly slow, ambush-based predator.

But given where it was found, the fact that there was enough prey to ambush it is perhaps even more shocking than the animal itself.

Location, location, location

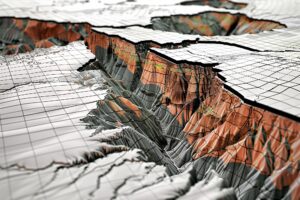

“The continents were organized differently 270-280 million years ago,” says Pardo. By then, a megacontinent called Pangea had already split into two supercontinents. The northern supercontinent, called Laurasia, includes parts of modern North America, Russia, and China. The southern supercontinent, home of gaiasia, was called Gondwana, which consisted of present-day India, Africa, South America, Australia and Antarctica. And Gondwana was quite cold then.

“Some researchers suggest that the entire continent was covered in glacial ice, similar to what we saw in North America and Europe during the ice ages 10,000 years ago,” says Pardo. “Others say it was more uneven – there were patches where there was no ice,” he adds. Yet, 280 million years ago, northern Namibia was about 60 degrees south latitude – roughly where the northernmost parts of Antarctica are today.

“Historically, we’ve thought about quadrupeds [of that time] they lived much like modern crocodiles. They were cold-blooded, and if you’re cold-blooded, the only way to get big and stay active is to be in a very hot environment. We believed that such animals could not live in a colder environment. Gaiasia shows that this is absolutely not the case,” says Pardo. And it turned a lot of what we knew about life on Earth upside down gaiasiait is time.