Times Insider explains who we are and what we do, and provides behind-the-scenes information on how our journalism comes together.

Katrina Miller was in her final year of a seven-year Ph.D. program in physics when she thought journalism might be written in the stars for her.

When she began her degree, she thought she might become a researcher or even a full professor one day, like many graduates of her program at the University of Chicago.

“Somewhere along the way, I think I realized that I really like learning and talking and doing physics more than being on the front lines of research,” she said in an interview. “In the sheer volume of it all, it was hard for me to stay excited.”

While pursuing her Ph.D., she contributed to Wired magazine and the University of Chicago website, covering physics. She developed a passion for reporting and in 2022 looked into the New York Times Fellowship Program for Early Career Journalists. On a whim, she put together clips from her articles, wrote a cover letter and applied.

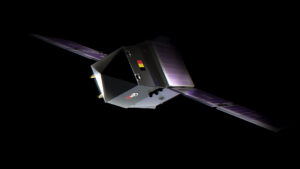

She was accepted into the program about a month later, much to her surprise. As a Science Desk Fellow, Dr. Miller covered a variety of topics, including the total solar eclipse in North America in April, China’s journey to the far side of the moon, and shape-shifting plastics.

After completing the one-year fellowship, she joined The Times in June as a full-time reporter. Its rhythm is expansive, literally—it includes physical sciences such as space, space exploration, and physics.

In a telephone conversation from her home in Chicago, Dr. Miller shared how her academic background has influenced her reporting and her goals for future coverage. These are edited excerpts.

What made you fall in love with science?

I grew up in Phoenix in a single parent household. It was just me, my mom and my brother. We were always in survival mode. I went to a very low-income public school, so I didn’t really have opportunities to go to space camp, for example.

When I look back, in retrospect, I think the signs were there. I have always been attracted to mathematics. But I never made the connection that astronomy or physics was something one could study and pursue as a career because I had never met an astrophysicist. The only scientist I could even conceptualize was Einstein. How do I treat someone as a black girl? The interest was there; I just didn’t have the resources to really cultivate it.

Then I went to high school and had the opportunity to take a physics class. When I entered college and discovered astronomy my freshman year and then took physics my sophomore year, I felt left behind in many ways compared to my peers.

How did your science training prepare you for a career in journalism?

As a scientist, you are trained to form a hypothesis. You collect data, analyze it and draw a conclusion. Then you have to follow what the data says, whether your hypothesis is right or wrong. I think this kind of scientific method is very similar to the journalistic method, where you have an angle, you talk to people, you collect data, and then you synthesize your report notes and follow where the data leads you, even if that means your angle is wrong.

How do you explain dense topics like the physical sciences to readers?

As a journalist, you are nothing without your sources. I found very early on that when I talk to scientists about their work, it really helps if they don’t know that I have a Ph.D.

The reason I am not disclosing this is that I serve as a bridge between the general public and academic research. I want the sources to speak to me the way they would to the general public, someone who has no knowledge of physics or space beyond high school or what they saw in a planetarium.

You have interviewed many interesting personalities from science, incl Walter Massey and Itasha Womack. Is there anyone you hope to interview one day?

Nia Imara. She is an astronomer at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She is an artist. She makes these wonderful paintings. I think there is this perspective that scientists are not creative. Scientists are left-brained, and creativity is for artists, actors and singers. But there are so many people I’ve met in the scientific community who are so creative, and it extends beyond hobbies. It informed their research.

I was really glad to be able to write a profile of Walter Massey. It was probably the hardest piece I’ve ever written. I had never written such an in-depth profile. I remember sending my first draft to my editor and he said, “That’s great, but it’s not a profile. You sum up his life. I realized I had to follow this guy for a few days. I had to notice the way he laughs, his hand gestures, the books on his shelf, what his home looks like, and how he interacts with people.

What are your goals for the future of your coverage?

Now that I’m here at The Times indefinitely, I’m thinking longer term—bigger projects, longer pieces. One of my New York Times bucket list items is to contribute to The Times Magazine.

And just more personal reports. I want to go to the field and talk to people. For a lot of scientific coverage, you can simply pick up the phone or interview via Zoom. I would love to see a rocket launch in person.

If you weren’t a science reporter, what beat would you choose?

If I wasn’t writing about science, and if I had the expertise to do so, I’d probably be a theater or art critic. I am a big theater lover. Chicago has a great theater scene. In another, parallel universe, I’m a cultural writer.