Take a look

Zintimate ground sloths, musk oxen, and short-faced kangaroos: All have gone the way of the drone, gone from the face of the Earth. This is just a sampling of the large mammals that are no longer with us. Of the 57 species of megaherbivores known to have existed 50,000 years ago, only 11 survive. That’s a dismal 81 percent extinction rate.

Defined as large-bodied land mammals with an average adult body mass of 2,200 pounds or more, today’s remaining megaherbivores include elephants, rhinoceroses, giraffes, and hippos. These animals play critical roles in their ecosystems, from dispersing seeds to managing the landscape.

Elephants, for example, reduce the density of trees and shrubs through their movement and feeding habits. These open spaces make way for plains animals such as antelope and zebra, while hollows and crevices formed by broken branches and felled trees create habitats for small mammals, insects and fungi.

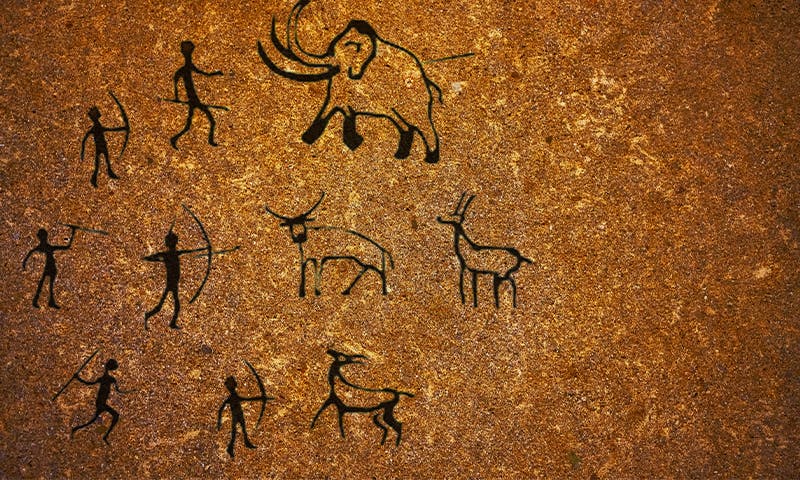

But these large creatures—which can’t hide under a log or move with the agility of a gazelle—were especially susceptible to early humans who wanted to get the most out of every hunt. After all, if you’re looking for meat to fill your belly and fur to keep your family warm, the woolly mammoth has a lot more to offer than the rabbit.

“We know that prehistoric humans were very focused on hunting large species,” says Jens-Kristian Svenning, director of the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Ecological Dynamics in the New Biosphere at Aarhus University. He is also the lead author of a recent article published in Cambridge Prisms: Extinction which argues that it was not climate change but rather human hunting that caused the extinction of most herbivores in the last 50,000 years.

The woolly mammoth has much more to offer than the rabbit.

To reach their conclusions, Svenning and his team analyzed ancient data on extinction, climate and human migration collected over the past six decades. The work continues a conversation that began in earnest in 1966, when an American paleontologist named Paul Schultz Martin first put forth his overkill hypothesis—in which he suggested that migrating humans chased Pleistocene-era North American megafauna to extinction. A few years ago, researchers published a paper in Nature who also found that the distribution of megafauna over time and space in prehistoric South America closely matched human demographics, as well as findings of spearheads called fishtails in the archaeological record.

“This is a long-term discussion,” says Svenning, who argues that improvements in research techniques and data quality in recent decades have helped us get closer to a definitive answer about how things turned out for the megafauna. “We have a much better understanding now than we did in the 1960s,” he says. “What we’ve done is reassessed all of that data and it allows us to say that, overall, we can really rule out that climate played a major role in this kind of extinction.”

Where and when the extinctions just don’t match global climate change patterns, according to the data the researchers collected and analyzed, but they do correspond closely with patterns of human colonization — occurring at or after our arrival at many different times and places along the world.

“We conclude that this is one of the strongest, most consistent patterns we have in ecology,” Svenning says. His team’s findings show that these megafauna extinction patterns began when humans first migrated out of Africa about 100,000 years ago. The extinction accelerated approximately 50,000 years ago when Eurasia and Australia were colonized by humans hunting big game.

Completing the business end of a spear had such a significant impact on large mammals because they have a naturally slow replacement rate. Gestation periods are long, as is the maturation process. The 46 species of megaherbivores that have been lost to history simply couldn’t reproduce fast enough to compensate for the human kills.

Felisa Smith, a conservation paleoecologist and professor at the University of New Mexico, believes that the human impact on megafauna extinction is no longer up for debate. “I think the work over the last few decades has shown pretty convincingly that humans had a pretty substantial role in the extinction,” says Smith.

This is not about assigning blame, says Svenning. “People who lived thousands of years ago never had access to the full picture. These things happened over long timescales and large spatial scales over which no one had an overview; whatever people did, it was hard to see the consequences. Besides, of course, people just had to survive as best they could.

Svenning hopes readers will take away a better understanding of the connections between humans and megafauna and the natural world. Large mammals remain highly vulnerable to extinction today, with over half of extant species weighing over 22 pounds listed as vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. “When we restore forests, we can’t just think about the trees,” he says. “We have to think about the animals that belong there.”

Main image: maradon 333 / Shutterstock