Prehistoric people hunted woolly mammoth. A growing body of research suggests that this species – and at least 46 other megaherbivore species – have been driven to extinction by humans. Credit: Engraving by Ernest Griese, photographed by William Henry Jackson. Courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program

Researchers from Aarhus University have concluded that human hunting, not climate change, was the primary factor in the extinction of large mammals over the past 50,000 years. This finding is based on a review of over 300 scientific papers.

In the last 50,000 years very large kinds, or megafauna, weighing at least 45 kilograms, are extinct. Research from Aarhus University suggests that these extinctions were primarily caused by human hunting rather than climate change, despite significant climate fluctuations during this period. This conclusion is supported by comprehensive reviews, including evidence of human hunting, archaeological data and studies in various scientific fields, demonstrating that human activity is a more decisive factor in these extinctions than previous dramatic climate changes.

The debate has raged for decades: did humans or climate change drive the extinction of the many species of large mammals, birds and reptiles that have disappeared from Earth over the past 50,000 years?

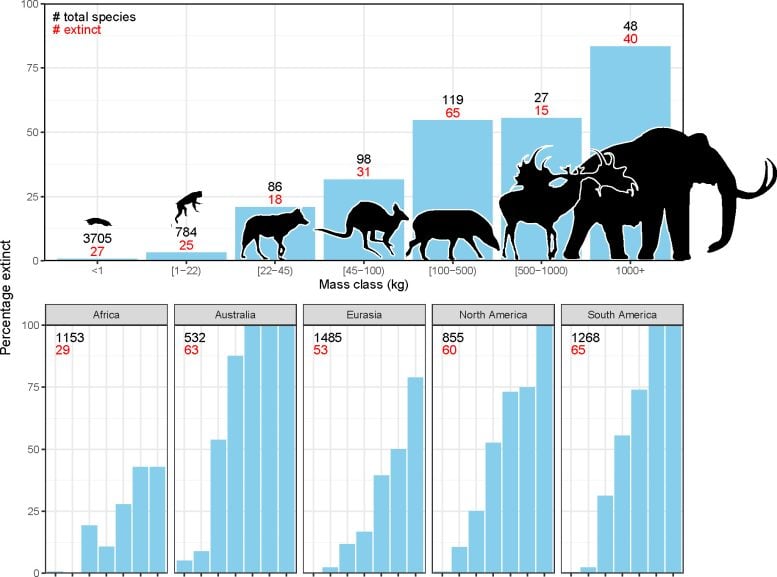

By “big” we mean animals that weigh at least 45 kilograms – known as megafauna. At least 161 species of mammals were driven to extinction during this period. This number is based on the remains discovered so far.

The largest of them were hit the hardest – the terrestrial herbivores weighing more than a ton, the megaherbivores. Fifty thousand years ago there were 57 species of megaherbivores. Today, only 11 remain. The remaining 11 species have also seen drastic declines in their populations, but not to the point of complete extinction.

A research group from the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Ecological Dynamics in a New Biosphere (ECONOVO) at Aarhus University concluded that many of these extinct species were driven to extinction by humans.

Jens Christian Svenning at a fossilized skeleton of a giant ground sloth, Lestodon armatus, on display at the Museum of Natural History, New York. Credit: Else Magaard, Aarhus University

Many different areas of study

They present this conclusion in a review article invited and published in the scientific journal Cambridge Prisms: Extinction. A review article synthesizes and analyzes existing research within a particular field.

In this case, Aarhus University researchers included several research areas, including studies directly related to the extinction of large animals, such as:

- The time of species extinction

- Dietary preferences of animals

- Climate and habitat requirements

- Genetic estimates of past population sizes

- Evidence of human hunting

In addition, they include a wide range of research from other fields necessary to understand the phenomenon, such as:

- Climate history over the last 1-3 million years

- Vegetation history during the last 1-3 million years

- Evolution and dynamics of the fauna during the last 66 million years

- Archaeological evidence of human expansion and lifestyle, including dietary preferences

Climate change played a smaller role

Dramatic climate changes during the last interglacial and glacial periods (known as the Late Pleistocene, from 130,000 to 11,000 years ago) certainly affected the populations and distributions of both large and small animals and plants around the world. But significant extinctions occur only among large animals, especially among the largest.

An important observation is that previous, equally dramatic ice ages and interglacials in the last few million years did not cause selective loss of megafauna. Especially at the beginning of the ice ages, the new cold and dry conditions caused large-scale extinctions in some regions, such as trees in Europe. However, there was no selective extinction of large animals.

This figure shows how the late Quaternary extinction of large mammals was related to their body size. At the top you can see the global percentage of extinct species based on their size. The lower part divides it into continents. The black numbers represent the total number of species that lived during that time, including those that still exist and those that have gone extinct. Red numbers indicate extinct species. Credit: Aarhus University ECONOVO / Cambridge Prisms: Extinction

“The large and highly selective loss of megafauna over the past 50,000 years is unique to the past 66 million years. Previous periods of climate change have not led to large, selective extinctions, which contradicts the major role of climate in the extinction of megafauna,” says Professor Jens-Christian Svenning. He directs ECONOVO and is the lead author of the paper. He adds: “Another important pattern that argues against a role for climate is that recent megafauna extinctions hit both climatically stable and unstable regions equally hard.”

Effective hunters and vulnerable giants

Archaeologists have found traps designed for very large animals, and isotopic analyzes of ancient human bones and protein residues from spearheads show that they hunted and ate the largest mammals.

Jens-Christian Svenning adds: “Early modern humans were efficient hunters of even the largest animal species and clearly had the ability to reduce populations of large animals. These large animals were and are particularly vulnerable to overexploitation because they have long gestation periods, produce very few offspring at a time, and take many years to reach sexual maturity.

The analysis shows that human hunting of large animals such as mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths is widespread and consistent throughout the world.

It also shows that species have gone extinct at very different times and at different rates around the world. In some local areas this happened quite quickly, while in other places it took over 10,000 years. But everywhere this happened after the arrival of modern humans, or in the case of Africa, after cultural progress among humans.

…in all kinds of environments

Species have become extinct on all continents except Antarctica and in all types of ecosystems, from tropical forests and savannahs to Mediterranean and temperate forests and steppes to arctic ecosystems.

“Many of the extinct species could have thrived in different types of environments. Therefore, their extinction cannot be explained by climate changes causing the extinction of a specific type of ecosystem, such as the mammoth steppe – which also housed only a few species of megafauna,” explains Jens-Christian Svenning. “Most species existed in temperate to tropical conditions and should have actually benefited from warming at the end of the last ice age.”

Implications and recommendations

The researchers point out that the loss of megafauna had profound ecological consequences. Large animals play a central role in ecosystems, influencing vegetation structure (eg the balance between dense forests and open areas), seed dispersal and nutrient cycling. Their disappearance has led to significant changes in the structures and functions of ecosystems.

“Our results highlight the need for proactive conservation and restoration efforts.” By reintroducing large mammals, we can help restore the ecological balance and support the biodiversity that has developed in megafauna-rich ecosystems,” says Jens-Christian Svenning.

Reference: “The Late Quaternary Extinction of Megafauna: Patterns, Causes, Ecological Consequences, and Implications for Ecosystem Management in the Anthropocene” by Jens-Christian Svenning, Rhys T. Lemoine, Juraj Bergman, Robert Buttenwerf, Elisabeth Le Roux, Erik Lundgren, Ninad Mungi and Rasmus Ø. Pedersen, March 22, 2024, Cambridge Prisms: Extinction.

DOI: 10.1017/ext.2024.4

The study was funded by Villum Fonden, the Danish National Research Foundation and the Independent Research Fund Denmark.