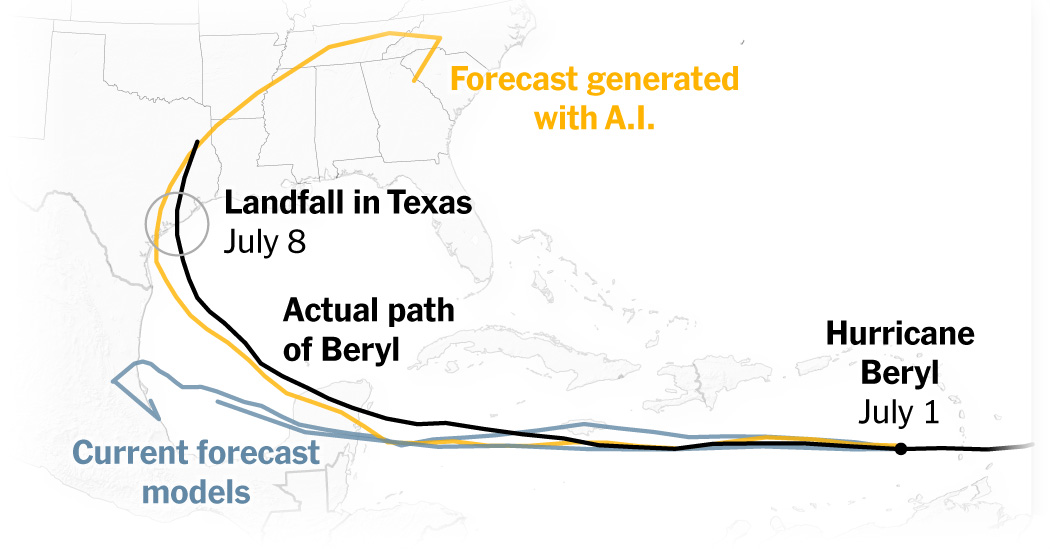

The National Hurricane Center (US) 5-day, ECMWF (European) and GraphCast models as of July 1, 2024 at 8:00 PM Eastern. All times on the map are Eastern.

By William B. Davis

In early July, when Hurricane Beryl swept through the Caribbean, a leading European weather agency provided for set of extreme droughts warning that this Mexico is most likely. The warning was based on global observations from aircraft, buoys and spacecraft, which room-sized supercomputers then turned into forecasts.

That same day, experts running artificial intelligence software on a much smaller computer predicted a drought in Texas. The prediction is based on nothing more than what the machine has previously learned about the planet’s atmosphere.

Four days later, on July 8, Hurricane Beryl struck Texas with deadly force, flooding roads, killing at least 36 people and knocking out power to millions of residents. In Houston, high winds sent trees crashing into homes, crushing at least two victims to death.

Composite satellite image of Hurricane Beryl approaching the Texas coast on July 8.

NOAA, via European Press Agency, via Shutterstock

The Texas forecast offers a glimpse into the emerging world of AI weather forecasting, in which a growing number of intelligent machines are predicting future global weather patterns with new speed and accuracy. In this case, the experimental program was GraphCast, created in London by DeepMind, a Google company. It does in minutes and seconds what once took hours.

“It’s a really exciting step,” said Matthew Chantry, an artificial intelligence specialist at the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, the agency behind its Beryl forecast. Overall, he added, GraphCast and its smart cousins can outperform his agency in forecasting hurricane paths.

In general, superfast artificial intelligence can excel at spotting impending hazards, said Christopher S. Bretherton, professor emeritus of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington. For the treacherous heat, winds and torrential rain, he said, the usual warnings would be “more relevant than now”, saving countless lives.

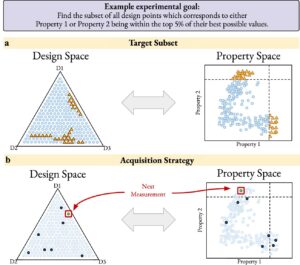

Rapid AI weather forecasts will also aid scientific discovery, said Amy McGovern, a professor of meteorology and computer science at the University of Oklahoma who directs the AI Weather Institute. She said meteorologists are now using AI to create thousands of subtle forecast variations that allow them to detect unexpected factors that can trigger such extreme events as tornadoes.

“This allows us to look for fundamental processes,” Dr McGovern said. “It’s a valuable tool for discovering new things.”

Importantly, AI models can run on desktop computers, making the technology much easier to adopt than the room-sized supercomputers that now rule the world of global forecasting.

Abandoned vehicles under an overpass in Sugar Land, Texas, on July 8.

Brandon Bell/Getty Images

“This is a turning point,” said Maria Molina, a meteorologist at the University of Maryland who studies artificial intelligence programs to predict extreme events. “You don’t need a supercomputer to generate a prediction. You can do it on your laptop, which makes science more accessible.”

People rely on accurate weather forecasting to make decisions about things like how to dress, where to travel, and whether to flee a severe storm.

However, reliable weather forecasts are proving extremely difficult to achieve. The problem is complexity. Astronomers can predict the paths of the planets of the solar system for centuries to come because a single factor dominates their movements – the sun and its enormous gravitational pull.

In contrast, Earth’s weather patterns arise from multiple factors. The planet’s tilts, turns, wobbles, and day-night cycles turn the atmosphere into turbulent whirlwinds of winds, rain, clouds, temperatures, and air pressure. Worse, the atmosphere is inherently chaotic. By itself, without an external stimulus, a certain zone can quickly go from stable to capricious.

As a result, weather forecasts can fail after a few days, and sometimes after a few hours. The errors grow in line with the length of the forecast – which today can last 10 days, compared to three days a few decades ago. The slow improvements come from upgrading global observations as well as the supercomputers that make the forecasts.

Not that working with supercomputers has become easy. Preparations require skill and labor. Modelers build a virtual planet intersected by millions of data gaps and fill in the blanks with current weather observations.

Dr. Bretherton of the University of Washington called the data conclusive and somewhat improvisational. “You have to blend data from many sources into an estimate of what the atmosphere is doing right now,” he said.

Complex fluid mechanics equations then turn the mixed observations into predictions. Despite the enormous power of supercomputers, processing the numbers can take an hour or more. And of course, when the weather changes, forecasts need to be updated.

AI’s approach is radically different. Instead of relying on current readings and millions of calculations, an AI agent draws on what it has learned about the cause-and-effect relationships that govern the planet’s weather.

Overall, the progress stems from the ongoing revolution in machine learning, the branch of AI that mimics the way humans learn. The method works with great success because AI excels at pattern recognition. He can quickly sort through mountains of information and notice subtleties that humans cannot discern. This has led to breakthroughs in speech recognition, drug discovery, computer vision and cancer detection.

In weather forecasting, AI learns about atmospheric forces by scanning repositories of real-world observations. It then identifies subtle patterns and uses this knowledge to predict the weather, doing so with remarkable speed and accuracy.

Recently, the DeepMind team that built GraphCast won the UK’s biggest engineering award, presented by the Royal Academy of Engineering. Sir Richard Friend, a Cambridge University physicist who chaired the jury, praised the team for what he called “groundbreaking progress”.

In an interview, Remi Lamm, GraphCast’s lead scientist, said his team trained the AI program on four decades of global weather observations collected by the European Prediction Center. “It learns directly from historical data,” he said. In seconds, he added, GraphCast can create a 10-day forecast that would take a supercomputer more than an hour.

Dr. Lam said GraphCast works best and fastest on computers designed for AI, but it can also work on desktops and even laptops, albeit more slowly.

In a series of tests, Dr. Lam reported, GraphCast outperformed the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Prediction’s best forecasting model more than 90 percent of the time. “If you know where a cyclone is going, that’s very important,” he added. “It’s important to save lives.”

A damaged house in Freeport, Texas, after the hurricane.

Brandon Bell/Getty Images

In response to a question, Dr. Lam said that he and his team were computer scientists, not cyclone experts, and had not evaluated how GraphCast’s forecasts for Hurricane Beryl compared to other forecasts in terms of accuracy.

But DeepMind, he added, did conduct a study of Hurricane Lee, an Atlantic storm that in September was considered likely to threaten New England or further east Canada. Dr. Lam said the study found that GraphCast anchored on land in Nova Scotia three days before the supercomputers reached the same conclusion.

Impressed by such achievements, the European center recently embraced GraphCast, as well as AI prediction programs made by Nvidia, Huawei and China’s Fudan University. On its website, it already displays global maps of its AI tests, including the range of path predictions the smart machines made for Hurricane Beryl on July 4.

The track predicted by DeepMind’s GraphCast, labeled DMGC on the July 4 map, shows Beryl making landfall in the Corpus Christi, Texas area, not far from where the hurricane actually made landfall.

Dr Chantry of the European Center said the institution sees the experimental technology as a regular part of global weather forecasting, including for cyclones. A new team, he added, is now building on the experimenters’ “great work” to create a working AI system for the agency.

Its adoption, Dr. Chantry said, could happen soon. However, he added that AI technology as a simple tool can co-exist with the centre’s legacy forecasting system.

Dr Bretherton, now a team leader at the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence (founded by Paul G Allen, one of the founders of Microsoft), said the European center was considered the world’s largest weather agency because benchmarking regularly show his predictions to outperform all others in accuracy. As a result, he added, his interest in AI led the meteorologist world to “look at this and say, ‘Hey, we should match this.’

Weather experts say artificial intelligence systems are likely to complement the supercomputer approach, as each method has its strengths.

“All models are wrong to some degree,” said Dr. Molina of the University of Maryland. AI machines, she added, “can make the right track of a hurricane, but what about rain, maximum winds and storm surge? There are so many different impacts’ that need to be reliably predicted and carefully evaluated.

However, Dr. Molina noted that AI scientists are rushing to publish papers that demonstrate new predictive skills. “The revolution continues,” she said. “It’s wild.”

Jamie Rome, deputy director of the National Hurricane Center in Miami, agreed with the need for multiple tools. He called AI “evolutionary rather than revolutionary” and predicted that humans and supercomputers will continue to play a major role.

“Having a person at the table to apply situational awareness is one of the reasons we have such good accuracy,” he said.

Mr. Rome added that the hurricane center has used aspects of artificial intelligence in its forecasts for more than a decade, and that the agency would evaluate and possibly use the smart new programs.

“With AI coming in so fast, many people feel that the human role is diminishing,” added Mr Rohm. “But our forecasters have a lot to contribute. There is still a very strong human role.”

Sources and notes

National Hurricane Center (NHC) and European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) | Notes: Beryl’s “actual track” uses NHC’s preliminary best track data.